[1]During the late 1800s, several German immigrants to Mexico came to Baja California to seek their fortune; Doña María Rieke’s grandfather, Eduard Rieke, was one of them. Adopting the Spanish name Eduardo, he arrived in La Paz in the late 1800s and made his way to El Triunfo to look for work. He met Fructosa Avilés in San Antonio, and they fell in love. She was married and had a son but left her husband for Eduardo.

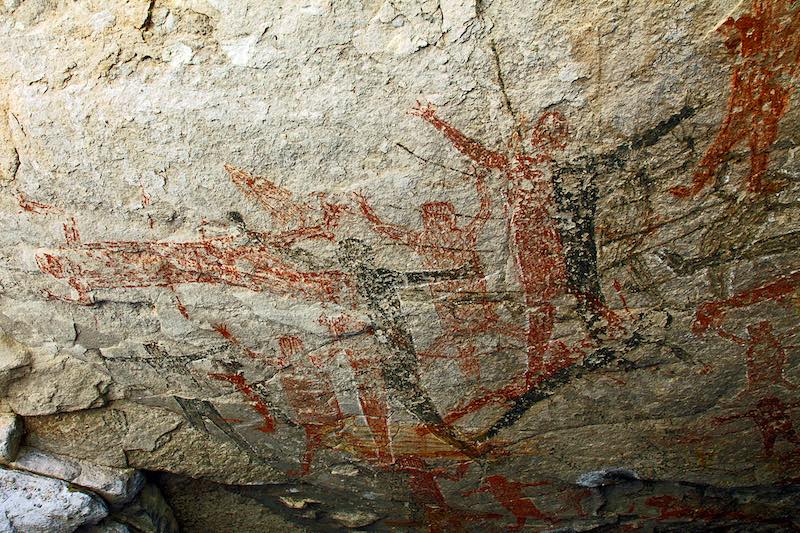

Eduardo learned about a Piedra Inscrita, Inscribed Rock, in the Las Canoas Arroyo above the Bay of La Ventana[2][3]. The rock held a clue to the location of a vein of gold discovered by Pericue Indians, which came to be known as La Tapada, The Covered [Mine]. Eduardo came to Las Canoas to search for La Tapada.

Continue reading “Doña María Rieke Verdugo, Ángel de Rancho Las Canoas”