[1]During the late 1800s, several German immigrants to Mexico came to Baja California to seek their fortune; Doña María Rieke’s grandfather, Eduard Rieke, was one of them. Adopting the Spanish name Eduardo, he arrived in La Paz in the late 1800s and made his way to El Triunfo to look for work. He met Fructosa Avilés in San Antonio, and they fell in love. She was married and had a son but left her husband for Eduardo.

Eduardo learned about a Piedra Inscrita, Inscribed Rock, in the Las Canoas Arroyo above the Bay of La Ventana[2][3]. The rock held a clue to the location of a vein of gold discovered by Pericue Indians, which came to be known as La Tapada, The Covered [Mine]. Eduardo came to Las Canoas to search for La Tapada.

Eduardo found the Piedra Inscrita, but not La Tapada. However, he saw potential in the Las Canoas Arroyo property, filed a claim for it, and wrote the date on a rock near the entrance to the Arroyo. Eduardo and Fructosa raised a large family at Rancho Las Canoas, including their colorful son Antonio.

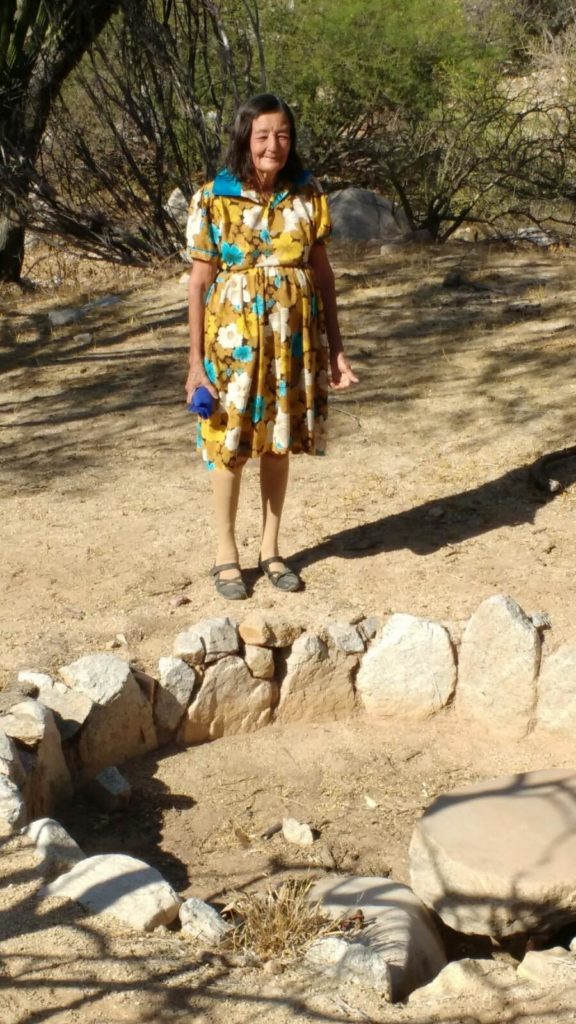

María Rieke was born at the Rancho on March 3, 1942, to Antonio Rieke and Vincenta Verdugo Avilés of Rancho Los Encinitos near El Ancon. Maria remembers helping with ranch work from a very young age:

We got up early to prepare coffee, grind corn by hand on a rock metate, and make tortillas. Sometimes we made pan dulce, sweet bread, if we had some flour and honey on hand. We hauled up buckets of water from a spring-filled cistern, milked the cows and goats, made cheese, cleaned our adobe and palm houses, did the washing, gathered firewood, and looked for wild plants ready to harvest. We picked a spinach-like plant for dinner called quelite, amaranth, that was abundant in the arroyos after summer rains. When native fruit was ripe, we enjoyed both sweet and sour pitahaya, ciruelos, plums, higos, figs, datils, dates, and sandlitas, passion fruit. We also hunted rabbits, pigeons, and quail. Sometimes, though, we only had enough food for two meals a day and went to bed hungry.

Besides raising cattle, running a small-scale gold mining operation, and occasionally fishing, Maria’s father kept bees and sold their wax to fishermen in El Sargento who used it to lubricate their boat riggings. Heavy rain sometimes damaged ranch property. After a summer cloudburst, the arroyo rumbled with the sound of water shoving boulders around like marbles. When the torrent subsided, all hands helped clear paths and repair damaged structures.

(Pitaya Dulce, Sweet Pitaya, ripens in the summer)

Maria recalls that while ranch life involved hard work, they made time for fun:

My father lugged a hand-cranked record player up to the ranch. We loved to listen to music and to my father sing and play the guitar. The highlight of the year was my Grandmother Fructosa’s birthday on January 21. People from El Sargento walked up to our ranch for the occasion. We played music and danced until after midnight[5].

My Abuela Fructosa outlived her husband but did not die at Las Canoas. Some of her sons were skilled cowboys and when needed, went to Todos Santos or Pescadero to amanzar bestias, tame horses. On one of these trips, Fructosa went with them but died before they could return. My own mother died in her early fifties, probably from the rigors of ranch life.

At the Rancho, we treated most illnesses and injuries ourselves. But if one of the younger women were pregnant and began labor, someone took an extra horse and rode down to La Ventana to get Prudencia Amador, who was a partera, midwife. I remember they brought her up there when my younger siblings were born.

(April 2017)

According to Gregorio Castro Calderón, around 1957 miners came to Las Canoas to explore for gold. Led by engineer Sebastián Díaz Encinas, they opened La Sonia mine, where they believed gold had been extracted before. This was at a place nearby called El Campamento, which María remembers visiting:

I took freshly-made cheese up to the miners to trade for beans and rice. Some people said that La Sonia was named after Señor Díaz‘s daughter. The only women I remember up there were the cooks. My father sold or traded the gold we found on our ranch property to buyers in La Paz or San Antonio. There was never much profit from our small operation.

Ernesto Rieke said that his father Enrique, one of Eduardo’s sons, told him that the first mines of Las Canoas may have been dug by Indians. He remembered a story about a ship that came to pick up a load of gold and pearls but was attacked by Indians before it could be loaded. They killed most of the ship’s crew, hid the treasure in a mine, and covered the entrance. Perhaps that was La Tapada. Sr. Enrique Rieke used his mining skills to excavate most of the wells in El Sargento, and others in La Ventana, El Teso, and nearby ranchos.

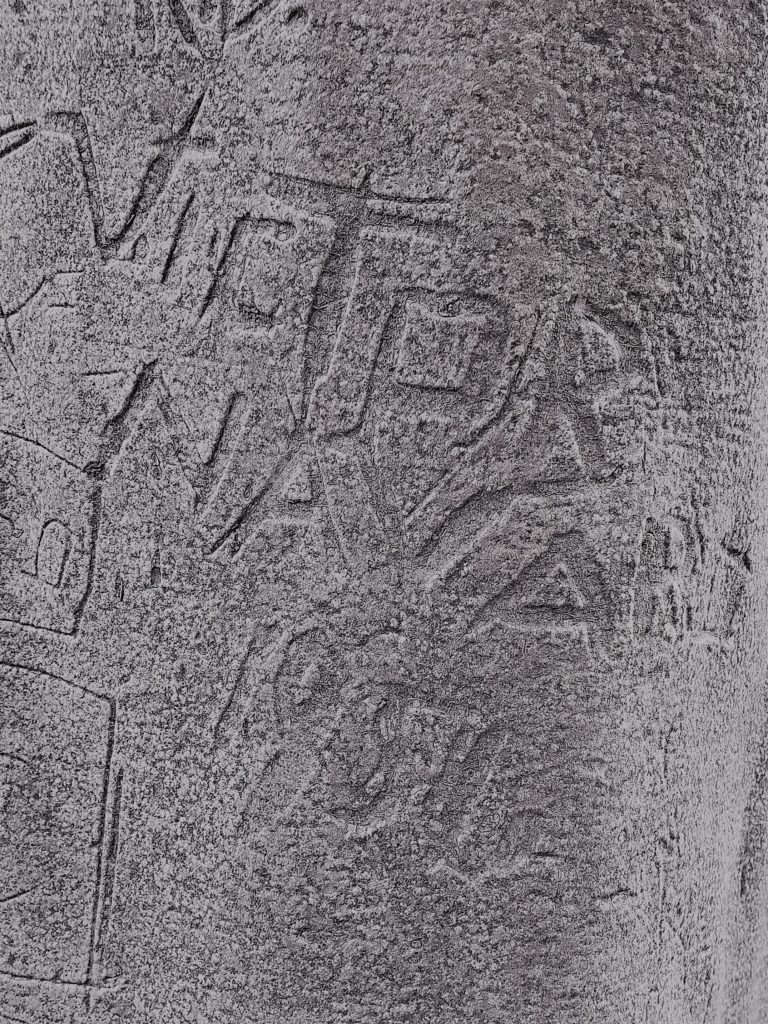

The rock face of the Shrine of Las Canoas in the photo above has a faint cross at the left and the name Jesus below it. At the upper right are the words Sor María[6] and under them the date año 1763 Agosto 3. I’ve been told there’s also the image of a ship. Can you find it? An explanation for Sor María is discussed in the endnote. But there is a second question: Who created the Shrine on August 3, 1763?

The Riekes may have been the first Europeans to settle the Arroyo, but it was a local indigenous group, the Pericues, who were the “first settlers“ and used it as a seasonal gathering place. Jesuit missionaries in Baja California sought out these Indian “Rancherias“ for new converts. Earlier converts took them to the Rancherias, so it appears that Jesuit missionaries visited Las Canoas and left evidence of their visit at the Shrine of Las Canoas.

María’s father, Antonio, was known as the Güero of Las Canoas because of his fair complexion. Although illiterate, he took care of the Rancho’s business in La Paz, sometimes using humor to his advantage as in these two stories[7]:

One time the Güero visited a friend in La Paz and suggested they sail to the Magote to pick wild plums. Antonio found a pair of panties under a tree and bet his friend that they belonged to his madre. Later, walking back to the friend’s house, two young ladies approached the men from the other direction. Antonio held up the panties and asked if they belonged to one them. Infuriated, one of the girls yelled pertenecen a tu madre prostituta, they belong to your prostitute mother. See, Antonio said, turning to his surprised friend, I think you owe me some money.

Another time, Antonio killed and butchered a neighbor’s bull that had wandered onto Rancho property. The neighbor had Antonio subpoenaed to court in La Paz. The deputy asked Antonio why he had slaughtered the animal. Antonio asked if the deputy had forgotten that he’d given him permission. I gave you a license to kill one of your bulls, the deputy answered. Delagado, the Güero replied, I can slaughter my animals anytime I want; I only asked because the beast on our property was not mine. The Güero left the court that day smiling.

There are legends about Victor Navarro, the cowboy of the Cacachilas,aka Don Diablo[8]. Less well known are the exploits of Doña María Rieke, Ángel of Las Canoas, if I can coin the expression. As she recalls here, her adventures were just part of living in the mountains:

Sometimes I walked or went by horse over dangerous trails through the sierra with my siblings to La Paz to sell gold and buy coffee, beans, and rice. On other occasions, I traveled alone from Las Canoas to San Antonio to see my cousin, Emilia. I’d start at 8 o’clock in the morning, stop at ranchos along the way, and arrive at my cousin’s place in the late afternoon.

I don’t remember my exact age when Victor and I started a relationship. He used to visit Las Canoas to look for work. Before we had children, we’d ride together hunting for deer and other game. I loved to explore the mountains with him, and we often rode double. With a hand from Victor, I’d swing myself onto a blanket behind the saddle and hold onto him tight. When my father got more horses, I rode my own.

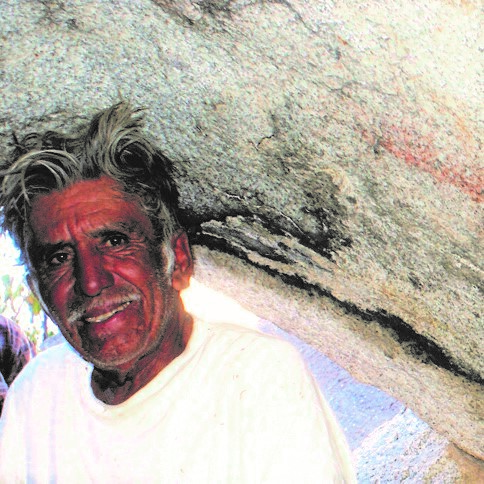

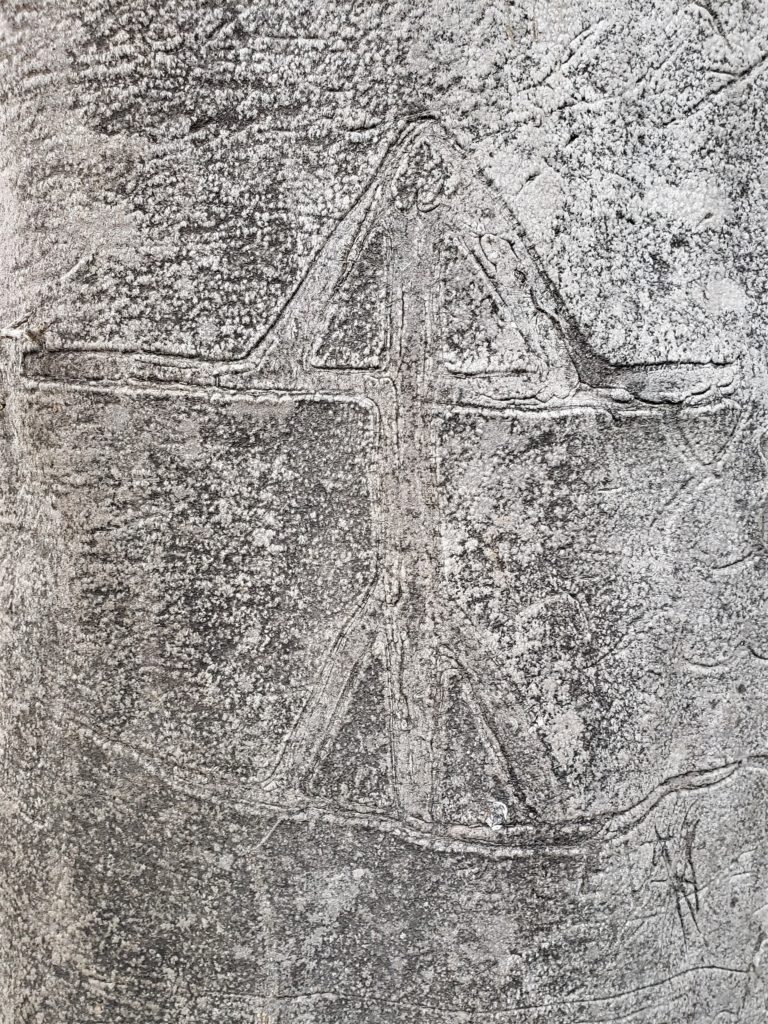

In 1958 when I was 16, Victor shot a wild pig. He followed it to a small cave, entered to remove the dead animal, and was astonished to find one wall covered with pinturas rupestres. I don’t think Victor was the first person to find the cave. Other people living in the mountains probably knew about it also. Two people lived in a cave near us during that time. They were friendly and had the features of Indians. The man was tall and had a prominent, curved nose. His wife was small and always wore a headscarf. They spoke Spanish with us, but between themselves, they spoke a language we did not understand. They hunted rabbits with slingshots, traded us gold for food, and sometimes helped in the mines.

(Notice the coincidental Baja-Penninsula shape at the lower-left outlined in black shading.)

(Photo Courtesy Aníbal López Espinoza, 2010)[9]

Victor and I had some favorite camping spots under big Palo San Juan trees. He chiseled his name on their trunks, carved images of animals and cattle brands, and chipped out figures, probably to get his bearings and remember where water could be found. After nightfall, we’d put the saddle blankets on the ground, pull palm fronds over us for warmth, and watch the stars and constellations pass overhead.

On one hunting trip, Victor dismounted by a tree that had round pods hanging among clusters of narrow leaves and picked a few to investigate. Something from the tree got in his eyes, and by the next morning, he was blind. It took a few weeks before his vision was completely restored. [The tree, actually a bush that grows up to 20 feet tall, is the Yerba de Flecha, the Poison Arrow Tree, and the pods are the famous Mexican jumping bean.]

I was not afraid of wild animals, but we tried to keep our distance from rabid ones. A mad fox bit one of my brothers who had to be treated in La Paz. Another time camping with Victor, I woke up to find a rattlesnake next to my arm. I kept as still as possible, but when I moved, the snake reared its head and shook its rattles. Finally, after what seemed like hours, it slithered off into the bushes.

Victor found work at San Antonio, but the job only lasted a few months, so he returned and stayed with me for a while. When I became pregnant, he promised to marry me but reneged later. He didn’t want to be tied down, but he always came back to me as I was the only person who accepted his way of life.

As the population at Las Canoas grew larger, it became more difficult to get by raising goats, gathering wild plants, and crushing rocks for diminishing amounts of gold. My aunt Ramona had 12 children and could not provide them enough food. They often went to bed hungry.

People began to leave the Ranch to marry or just to find a job. I was one of the last to stay. I raised goats and made a small amount of money selling meat and cheese in El Sargento.

One day I returned from the village and found my hut had burned down. I had three boys to care for as well as my father, whose health was deteriorating fast. I decided to move us all to a shady palo verde tree close to the beach near the village. I stretched out a rope around our campsite so the cows wouldn‘t trample us while we slept. Not long after we moved, my dad died.

We didn’t get much help from the older residents of El Sargento, who considered people from Las Canoas to be backward. I think we were looked down on because we hadn’t attended school. Even relatives who had moved down earlier and married Ejido members treated us as lower class. One time it turned so cold I asked a lady in town if we could stay in an empty room she had, but she turned us away. I was able to earn a small amount of money washing clothes and doing other domestic jobs, barely enough to get by.

Kiki Lucero saved us by giving me a job taking care of his livestock for 800 pesos a month. I got up at 3 o’clock in the morning, took a container of hot coffee with me, and walked up to the corrals where I fed the animals, milked the cows and goats, and cleaned up the place. If I hadn’t found work, we probably would have starved to death.

One time Victor resorted to drastic measures to help his homeless family. He rounded up and sold two cows for a rancher but made off with the money. The owner reported the theft to the authorities in La Paz; they found Victor and put him in jail. That’s when he made his famous escape and led the police on a chase through the mountains he knew so well. He even “borrowed” food from the sleeping posse at night. They never caught him. That’s probably how he got his nickname of Don Diablo, Devil.

Around this time, Victor decided to go to Tijuana to look for work. He spent one year there but never had enough success to send Maria any money. In the meantime, Maria’s oldest son, Javier, got a job working as a fisherman to help the family financially – he was only 11 years old.

Maria remembers this was when their life began to improve:

Relatives finally helped us get warm clothes and shelter. Eventually, we got a piece of land and built a little hut out of cartón on it, which I painted blue. We tried for several years to get the CFE to extend the power lines out to our home. Finally, Eli and Federico, windsurfers from Germany, bought property nearby and got them to bring electricity north of the village, making our lives much more comfortable.

My father inherited Rancho Las Canoas, but as he was illiterate, he left the title papers and power of attorney with a cousin who lived at Rancho Dos Hermanos. Many years after my father died, the property was sold to an American for 25 million pesos, as I recall. The cousin claimed all the money went to pay for my brother’s heart treatment in Mexico City. We never received a cent. Unfortunately, my brother died just a few days after returning home.

My father’s cousin had always been poor, but he no longer works and now lives in a large house in La Paz. I continued to get by caring for cattle and doing domestic jobs for Americans until I became too frail to continue working. I’m proud I can recall these events from the past and contribute to this story about Rancho Las Canoas.

Old-timers in La Ventana and El Sargento remember when hiking to Rancho Las Canoas was an annual event until access to the arroyo was fenced off. However, if you use your imagination, I’ll take you there. We’ll drive up the road from El Sargento that Maria walked so often, then hike the last quarter-mile to the entrance of the upper arroyo. Watch your step when you climb through the gap in the rock wall and enter a lush valley splashed with desert green.

Follow me around the boulders, and across the meandering stream, but be careful where you put your feet – rattlesnakes live here. Watch for Xantus’ hummingbirds, the only endemic hummers in Baja. We will stop at the Shrine of Las Canoas under the giant fig tree ahead on the right bank. There are some boulders to climb over before we arrive at the ruins of the Ranch. Someday, I hope a memorial plaque will be placed here to honor Maria and the Riekes, the First Family of Las Canoas.

After dinner at the Rancho campground, we‘ll dance to music from a hand-cranked record player. Before we head back down, close your eyes and listen for a voice from the past coming from one of Victor and Maria‘s camps. As darkness falls and the constellations begin to sparkle overhead, one of them sings a popular Mexican bolero of the time:

Now we own all the stars

And a million guitars

Are still playing.

Darling, you are the song,

And you’ll always belong

To my heart

Note: Rancho Las Canoas is private property, part of Rancho Cacachilas. Guided hikes and bike rides ending at Rancho Las Canoas can be arranged at the Bike Hub in El Sargento, or the Rancho web site. Hopefully, a walk to Shrine of Las Canoas, as described above, will be offered someday by Rancho Cacachilas.

Tom at BajaNightSky@gmail.com

Footnotes

- A story constructed from background material and interviews with Maria Rieke by Elisabeth and Federico Weiland, and Tom Spradley.

- From a 2006 interview with 70-year-old Gregorio Castro Calderón by Josue Sanders (married to Julia Rieke)

- When we asked Maria if she knew where the name Las Canoas came from, she told us to hike up to the very end of the canyon where there is sometimes a waterfall. She said if we climb up to the base of the waterfall, we will find the canyon narrows to point just like a canoe. Other former Las Canoas residents have told us there is a rock above the floor of the arroyo with drawings of canoes.

- After Inocencio Rosas Castro from El Sargento married Socorro Aguilar from Rancho Las Canoas, he shouldered this heavy rock metate Socorro had grown up using and carried it more than 6 miles down the arroyo to their outdoor kitchen in El Sargento.

- Told to Tom & Louise Spradley around 2008 by Anolfo and Anilita of El Sargento who attended the dances.

- “Sor María” means “Sister María,” but in 1763 Sor María was someone special to Jesuit missionaries in the New World. She had lived in Spain in the 1600s. At a young age, she began to have mystical ecstasies. She wanted to go to the New World as a missionary, a role filled mostly by men in those times. She became a nun and convinced her rich father to convert the family estate into a convent so she would not have to leave home. She became one of the 10 most influential women in Spanish history, a trusted advisor to King Felipe IV, and author of many books. Though she never left Spain, she believed she had traveled to Mexico during trances and converted the Jumano Indians living along the Rio Grande, and Jumano Indians reported many visits by a lady dressed in blue. Each year the Jumanos celebrate these visits at a festival that honors The Lady in Blue. In 1763 Jesuits were still exploring remote areas of Baja looking for Indian Rancherias and new converts. They looked to the story of Sor María for inspiration and strength. On August 3, 1763, it appears that someone visited this place and created the Shrine of Las Canoas.

- Crónicas: La Paz y sus Historias, “El Guero del Rancho las Canoas,” Noticalifornia: “El Güero de Las Canoas y el Novillo Perdido”

- The Don Diablo Trail Run was named after Victor Navarro.

- When author Aníbal López Espinoza was tracking down and photographing the rock art of the Cape Region for his book Evocaciones del Olvido (Reminders of a Forgotten Past – 2013), Victor Navarro took him to the cave paintings he had discovered in the Sierra de Las Cacachilas.

- Several of the Palo San Juan trees Victor camped under have been discovered by Chuck Murphy. The species, which has Federal protection, live hundreds of years and produce edible fruit. Victor Navarro’s name and the date are carved in many of the trees. He also left works of art, arborglyphs, on some, a tradition of Basque sheepherders in the United States, and apparently of at least one Baja cowboy.