Introduction

The pueblo of El Sargento in Baja California Sur overlooks the Bay of La Ventana and Isla Cerralvo, the rugged, uninhabited island seven miles offshore. In 1998, the quiet fishing village had a population of around 800.[i] A dozen foreigners had built homes close to the beach below the washboard road going north from town. They bought their groceries from Armida at the one-room market in her mother’s house across from the church plaza. You could have a delicious Mexican meal at Tacos Leon for as little as two dollars. The place was so popular, people often had to wait outside for the “second sitting.”

Ten concrete-block homes lined the narrow dirt road that winds through the pueblo. Mexican families enjoyed sitting outdoors on their verandas, eating dinner, visiting with neighbors, and watching children play in the street. When the newcomers drove by, out of common courtesy they slowed to a crawl to avoid causing an injury or leaving residents choking on clouds of dust. A few recent visitors, however, seem to be in such a big hurry that they forget they are guests in another country. They careen through the zigzag as though competing in the Baja 1000. They must be going someplace more important than respect for La Gente, the Mexican people who live and work here.

The campground at the pueblo’s sister village 5 km to the south, La Ventana, was a winter haven for a few hundred windsurfers. That was about to change. La Ventana’s first kiteboarder hit the water in 1998 with a two-line kite and a broken seven-foot surfboard he had glued back together. The combination was a sight foreign to most people that day, but it changed the bay forever. That was my son, Bruce. Soon there would be more kites in the sky than sails on the water.

The two villages provided only essential services for visitors. If you needed gas for a trip to La Paz to fill up, go shopping, or check email at an internet cafe, you stopped by Juan Ramon’s hardware. Juan or Alejandro Rieke pumped a few gallons of gasoline from a barrel to get you there. And if you spoke some Spanish, they had some interesting stories to share.

Juan Avilés Avilés, who lived in a house in La Ventana decorated with chocolate clamshells, owned the only phone in town, a shoebox-size cellular. Juan had a wireless monopoly and charged ten pesos a minute, which he timed with a stopwatch while you made a phone call from his sofa. His neighbors called him Juan Lana, the equivalent of “Moneybags John.”

Nowadays, it’s not unusual for old-time visitors, to complain that twenty years ago, times were much better: fewer people, less traffic, less late-night noise, and no new home or business blocking a cherished view. I imagine many Mexicans who have always lived here feel the same way.

Along with more people came more outdoor illumination and the misconception that light at night provides security for homes and is attractive for businesses. Properly shaded fixtures that direct light down where it is needed do, but unshielded lights produce polluting glare, attract unwanted attention, and rob everyone, especially the children who grow up here, of the awe-inspiring night sky. The gains made against light pollution with the new night-sky-friendly street lights are being lost to bare-bulb strings of hanging lights that make a property look like a cheap Christmas-tree lot. La Ventana and El Sargento cannot gain International Dark Sky status without everyone, campers, homeowners, and businesses, using only night-sky friendly outdoor lights [ii].

Change has required new legislation making it illegal to block access to beaches or drive ATVs on them, dump trash and construction debris in arroyos, and put up unshaded outdoor lights, laws designed to protect turtle habitat, the bay, the night sky, and people. Young and old have organized to protect access to beaches and the night sky, enforce the ban on driving ATVs on beaches, clean up trash from the highways, eliminate the use of plastic bags, provide funding for schools, the handicapped, and the ambulance team, recycle cans, glass, and paper, fight global warming by reducing the consumption of meat, care for animals, and support other worthy causes. Maybe we are just beginning the best of times. [iii]

- [i] Gilberto Ibarra Rivera (2016), Diccionario Sudcaliforniano: Historia, Geografía, y Biographías de Baja California Sur

- [ii] See resources at www.darksky.org

- [iii] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/10/opinion/how-to-help-climate-change.html?auth=login-email&login=email

Who Was El Sargento?

El Sargento’s earlier past is murky. It was once called La Flecha, for the arrowheads people found along mountain trails and on the bluffs above the shore. Opinions differ on how the town acquired its present name. Justiniano Lucero[i] recalls hearing that “A ship called El Sargento got caught in bad weather here, went aground, and broke up in the pounding waves. It was for this reason they called the place El Sargento.” Another version of the story suggests the name honors a Sargento from the shipwreck, who washed up on shore dead. The grave next to the old Centro de Salud is supposedly where he is buried.

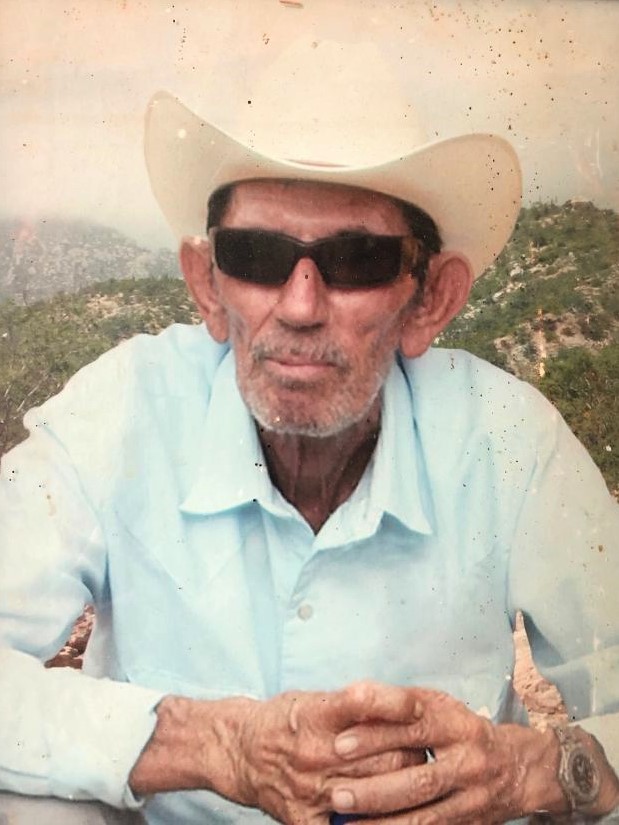

(Photo courtesy Sharon Bishop)

A third story for the origin of the town’s name requires some explanation. Fishermen, pearl divers, and sailors visited the region as early as 1816 to quench their thirst at El Pozo del Sargento, The Sergeant’s Well. [ii] It was probably located near the palmar, palm grove, next to Las Palmas Restaurant, which provided a sheltered place for a canoe or ship’s boat to land near the well. Nowadays, surfers or Minnesotans are more likely to visit the watering hole at the Restaurant and quench their thirst with a few beers or margaritas.

The third story, mentioned above, involves a sergeant Spain posted here in the early 1800s to watch for ships flying a Dutch, English, or freebooter flag. If the lookout spotted one, he warned the garrison in La Paz. Perhaps homing pigeons carried the message, or maybe the sergeant took it himself, running through the mountains on Indian trails. Even today, a few aging marathoners make the run in the opposite direction for no apparent reason other than to reenact history, a brave and noble act requiring many hours of training.

Believe what you wish—shipwreck, dead sergeant, or lookout’s well. If you find none of them convincing, a vacationing birdwatcher once suggested to me that the pueblo was named for the El Sargento Bird, a migratory species that frequents these parts during the winter mating season. In any case, for one reason or another, people started calling this place El Sargento.

- [i] From Josue Sanders Interview with Justiniano Lucero Aviles, age 84 (2006)

- [ii] Gilberto Ibarra Rivera (2016), Diccionario Sudcaliforniano: Historia, Geografía, y Biographías de Baja California Sur

The First Colonists

Schemes to attract buyers to nonexistent resorts on the Bay of La Ventana are not original with twenty-first-century scammers. In 1862, The Lower California Colonization and Mining Company of San Francisco lured settlers here with outright lies about a colonial town on the shores of the Bahía de la Ventura, Bay of Treasure. The shrewd promoters did not think Bahía de la Ventana, Bay of the Window, was seductive enough to sell a fool’s paradise.[i]

The colonial town the company was “building” was said to be surrounded by 125,000 acres of fertile, well-irrigated land producing a variety of fruits and vegetables. A network of roads made it easy to sell a bountiful harvest to miners in nearby San Antonio and El Triunfo. The sea and mountains had pearls, gold, and precious stones for the taking. There were verdant woodlands and streams. It must have all been true because it was shown right on the promoter’s maps. All that was missing was kitesurfing, pizza, and a website, but those would inevitably follow in 150 years. Despite these fanciful claims, people invested money and signed up to colonize the new town. After all, there were persistent rumors that the United States would soon acquire Lower California, instantly making the land soar in value.

After a miserable voyage of 27 days, when the seasick colonists disembarked, all they found was a parched and prickly desert—no city, no fertile farmland, and no water or food. The disillusioned colonists had to dig in the arroyos for water as they made their way through the hostile desert to San Antonio. Most, if not all of the vagabonds, ended up in La Paz, a city of some 800 souls, and begged them for passage back to San Francisco.

(Do you see yourself in this sketch?)

[i] Browne, J. Ross (1862) Explorations in Lower California 1868 in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, November 1868 pages 744-746

The First Settlers

In the 1750s, Manuel de Osio used his pearling fortune to develop the first privately-owned cattle ranch in Baja California, near San Antonio. His success attracted others into raising livestock, and the number of ranchos grew steadily over the next 150 years. One of them was Eduardo Rieke’s Las Canoas Rancho in the mountains above El Sargento; there were others within a day’s walking distance of the village.

Beginning around 1909, a trickle of ranch hands made their way to El Sargento. They came from Las Canoas, Agua Amarga, Punta Perico, and Bahia de Los Muertos, Bay of the Dead, where ships docked to unload supplies and pick up cattle for the mainland. A few disenchanted mineworkers came from El Triunfo. One family of mountain homesteaders arrived from the rugged valley-and-ridge enclaves a few miles northeast of El Triunfo, where some of the region’s finest alfareros, potters, developed their art. They all shared a desire to build a better life for their families. Many of the newcomers were Luceros, “bright stars” in Spanish, cousins of some degree who brought the energy of bright stars to the growing village.

Tia María

María Beltrán Lucero, who came to be known by everyone in El Sargento as “mi Tía María,” was born in 1928 in the pueblo of Agua Amarga. When María was an infant, her parents went north to Ensenda to look for work. Her grandparents, Don Pedro Lucero and Doña Jerónima Lucero, cared for her at nearby Punta Perico. Don Pedro fished and cared for cattle for Toribio Geraldo, one of the wealthiest ranchers in the area.

One day, Don Pedro and his son, Justiniano, paddled across the bay to look for a route to La Paz since there were no roads to the city at that time. They pulled their canoe ashore at the palmar below the Sergeant’s Well. Nearby, they met Juan Avilés, who had a vineyard, and a garden of vegetables and watermelons. Juan encouraged Don Pedro to join the small community and enjoy the easy access to La Paz to purchase beans and flour.

Don Pedro took a look around and agreed with Juan. He could provide a better life for his family here than rounding up stray cattle for a rich man at Punta Perico. So in 1932, Don Pedro canoed across the bay again with his wife and four-year-old granddaughter. He built a shelter for the family out of fallen cardón trunks, palo de arco branches, adobe, and palm.

Not long after Don Pedro got settled, his son Justiniano followed. When he arrived, Pablo Castro was already living here. Later, Ramon Avilés and Cuco Calderon arrived. All of the new arrivals brought skills they could share to make their neighbor’s lives more comfortable. Little by little, the village of El Sargento was formed.

Victoriano

In 1944, twelve years after Don Pedro and his family settled in El Sargento, the Cosio Arellano family arrived from El Triunfo. Jobs were scarce in the silver-mining town, so the family had decided to look for work as fishermen. Don Pedro offered them food and a place to sleep while they got established. His granddaughter, María, was now a young lady of sixteen, and she caught the eye of a member of the new family, an attractive boy named Victoriano.

María and Victoriano fell in love, and a short time later, they married. Lupe Angulo helped them build their first home, where they lived for the next eight years. María excelled at cooking and decorated the inside of her home with shells, driftwood, and flowers. Victoriano could row a dugout canoe to Isla Cerralvo, load it with a fresh catch, and return home the same day. When a gust of wind knocked over candles burning in the couple’s home, a fire destroyed the palm roof and damaged the interior. With the help of friends, Victoriano soon made the home livable again.

Treasures from the Sea to Build a House

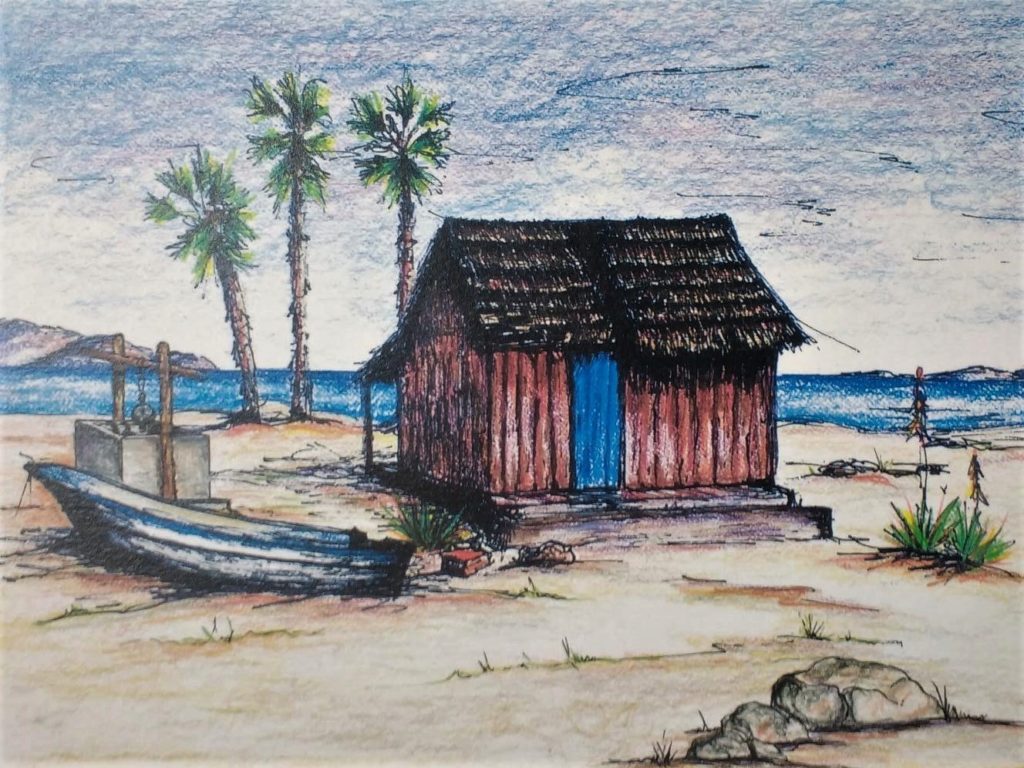

By 1953, the couple had several children and needed a more substantial house. Victoriano had found some wooden planks from a shipwreck off the shore of the island. Whenever he fished there, he filled his canoe with whatever he could salvage: wood planks, nails, screws, and on one voyage, a large pulley. Victoriano used the planks for the new casita’s walls, decay-resistant palo amarillo for the foundation, and adobe bricks for the floor. When he ran out of wood from the sea, he sold two cows to buy lumber to finish the walls and entrance. He painted the door blue, the color of the sea and sky that he so admired.

Sketch by Louise Spradley

Food and Water

The early settlers of El Sargento eked out a living from the sea and desert. When they wanted meat, they rowed out to the island and killed a few goats or trapped kids to raise back home. They fished and dived for sea turtles, which they sold or traded. From the desert, they gathered wild plums and pitahaya fruit. They hiked into the hills, fell and cut up palo blanco trees, carried the logs home, peeled the bark off, let it dry in the sun, and sold it to ranchers for tanning animal hides.[i]

Around 1960, the well water began to turn brackish, so Victoriano started digging a new one a few meters north of his home. He excavated a chest-high hole and shored it up with wood. After several months of work, hauling dirt and rock out using the pulley he had salvaged from the sea, he reached a depth of eight meters—without finding water.[ii]

On a warm Wednesday, Victoriano worked until noon. His heart pounded as he wiped the sweat from his brow, lifted the pick over his head, and smashed it into the earth. He gasped and let out a shriek of pain. When he realized he had driven the pick through his left foot, he yanked it out of his bloody flesh and broken bone, secured the rope around his waist, and called for his friends to haul him up. As they pulled him out of the well, he fainted.

Fortunately, there was an automobile in the village that day. After cleaning and wrapping the wound, Victoriano’s friends loaded him into the car. The driver headed up the road to Las Canoas, the only way out of the village, crossed over to the windy camino from Los Planes to San Antonio, and made the dangerous three-hour trip from there to La Paz for medical care.

Victoriano recovered and continued his work, but when a chubasco hit, water overflowed a nearby gully and washed the excavated earth back into the hole. After another year of digging in his free time, he struck water at a depth of twelve meters. He filled the bottom of the well with a layer of gravel, finished lining the walls with brick and mortar, built the cap, and reinstalled the pulley from the shipwreck.

Everyone turned out to celebrate the completion of the well. When the first bucket of 1961-vintage water was hauled up, the villagers offered a toast to Victoriano and Maria and carried large containers of the water back to their homes.

- [i] Josue Sanders interview with Gregorio Castro Calderón, 70 years of age (2006)

- [ii] Well digging story provided by María’s daughter (2006) The house had to be torn down in 2016.

Terremoto!

Justiniano Lucero never forgot the earthquakes that shook the bay in April of 1969: [i] “We kept tubs of water from Victoriano’s well in our house for cooking and washing. When the shaking started, the water sloshed out onto the ground. Sections of arroyos on the island collapsed, sending boulders crashing to the bottom and dust billowing into the air, hiding the island from sight. A part of the beach called Carapachos, the back of a tortoise, was mostly underwater after the shaking stopped.” The earthquakes were stronger on Cerralvo where the epicenters are just a few miles off of the island’s northeastern coast. [1]

After that earthquake, Esteban Lucero, a thirty-two-year-old fisherman living in El Sargento, looked across the bay as dust rose into the sky over the island. He wondered if Daphne and Dana had survived the earthquake. By April of 1969, sixteen-year-old Daphne had been living on Cerralvo since the age of thirteen. El Sargento fishermen called her La Caballera de Cerralvo, The Horsewoman of Cerralvo, but Esteban Lucero knew her and her nine-year-old visiting friend, Dana, as friends. If they were injured, they needed his help. A storm coming up the gulf from the south was already bringing strong winds and kicking up whitecaps on the bay. It was not safe to paddle his fishing canoe to the island. All he could do for now was pray.

- [i] From Josue Sanders Interview with Justiniano Lucero Aviles, 84 years of age (2006).