A Fisherman’s Life

Guillermo

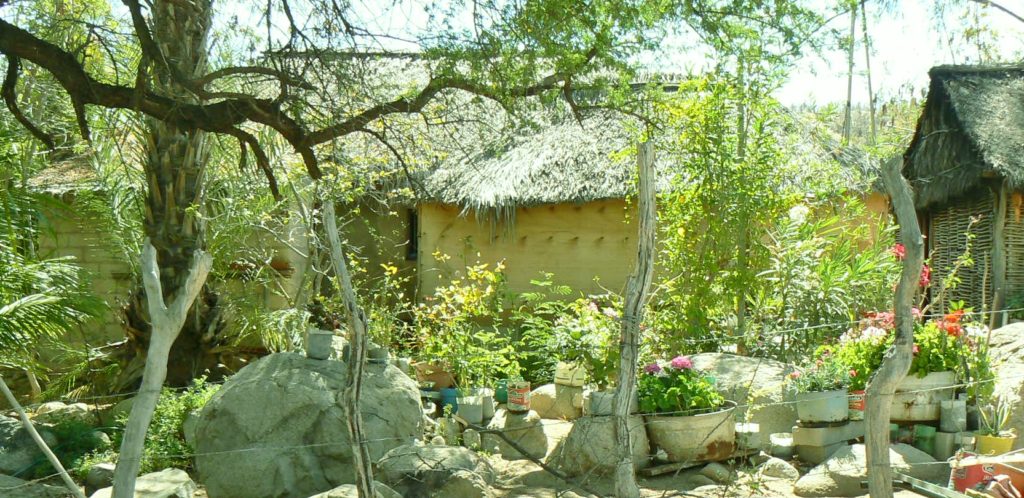

The mountain range just south of San Juan de Los Planes is called the Sierra la Gata. A century ago, there was a narrow trail that went over the mountains and connected Los Planes to Boca de Alamo, a tiny fishing village on the Sea of Cortez. (Today that trail is a narrow road, often with washouts that make it impassable by auto.) Manuel Avilés Geraldo traveled by burro over the trail from Los Planes to trade or sell cheese and vegetables to the residents of Boca de Alamo and La Reforma, the beautiful hacienda three miles west of Boca de Alamo near some impressive ancient rock art. At La Reforma, he met Señorita Adelia Lucero. Señor Avilés sometimes paddled a canoe across the Bahía de Los Muertos and walked up to La Reforma to court her. After they married, he brought his wife and mother-in-law to the home he had built in Los Planes [1], a Mexican shack called a jacal that had a palm-thatch roof, mud-plastered palo-de-arco walls, and dirt floor. Señor Avilés cared for cattle at Punta Perico and toiled in the mines at Las Canoas to support a growing family. Guillermo Avilés Lucero, the youngest of the family’s five siblings, was born in July 1947—a month after his father had died.[2]

[1] The South Territory of Lower California became the state of Baja California Sur in 1974.

[2] This story was developed from multiple interviews with Guillermo Lucero beginning in 2009 to the present.

Misfortune

When Guillermo was eight years old, he rolled a log over while exploring outdoors and discovered a small snake. Curious, he picked it up, and the baby rattler bit him. His mom borrowed a car to take him to La Paz. Four hours later, after bumping over the washboard road through San Antonio, they arrived at the hospital in La Paz with Guillermo in pain and struggling to breathe.

Guillermo doesn’t recall if the hospital had antivenin back then, but he remembers spending four weeks recovering from the snakebite. He’ll never forget what happened next:

The day after I returned home, I went out to help my mom. She was splitting a log with an ax when a stray woodchip struck me in the eye. I screamed, and my vision started to blur. Our village didn’t have a doctor, and we couldn’t find a car to borrow for another trip to La Paz.

I went to class the next day, but my eyes hurt every time I tried to read. After listening to my complaints for several weeks, the teacher told me that school was bad for my vision and sent me home. I never went back. I enjoyed learning, and I had earned good grades, but now I was stuck at home. I finally saw a doctor, but it was too late–I’d lost my sight in one eye, and there was nothing medicine could do about it.

A few weeks later, Guillermo and his mom went to the mountains to gather herbs. She cut her hand on a thorn, it got infected, and she died within a month. Devastated by the tragic loss of their mother, the family struggled to stay together and survive. One of Guillermo’s chores was keeping the sibling household supplied with firewood for cooking.

Gringo

In 1957 some Americans started flying into Los Planes to pick up fresh vegetables for markets in the United States. One day, ten-year-old Guillermo learned that the airplane had landed, so he walked over to the dirt airstrip on the northwest side of town to take a look:

That was the first time I’d seen an airplane up close. I watched fieldworkers load boxes of produce into the cargo bay. One of the Americans, a friendly man by the name of Kenny, approached me and struck up a conversation in Spanish. After I explained why I was not in school, he said if I’d drop by another time, he’d teach me how to drive the car they used to go into town.

The next day, after some instruction and practice, Kenny asked if I’d drive to the market and buy some food for them. Other times I went to get oil or something else they needed. After making a few trips, Kenny asked if I’d like to earn some money. With a big grin, I answered claro que si, of course, and started working for 13 pesos a week, the first money I had ever made.

Kenny didn’t always grasp the Spanish used by the Cholleros, the farmhands born in Baja California Sur who had grown up using the Spanish dialect left by the early explorers. It had slowly evolved to meet the needs of rancheros, farmworkers, and others. If Kenny didn’t catch what someone said, I’d explain it to him. Acting as a straw boss, I’d pass on orders from Kenny to workers in the fields and report back on how everything was going. That’s when my friends started calling me Gringo. The nickname has stuck with me ever since then. [3]

The Americans flew in to pick up produce twice a week. When the plane arrived, Gringo drove a truck loaded with boxes of vegetables to the airstrip, helped unload them, then returned to the fields for more.

One time, Kenny invited Guillermo to fly to Cabo San Lucas with them. Gringo thought better of the idea:

I never got aboard that airplane, not even to take a look around; I was afraid they would take me to the United States and never come back. The next year, Kenny’s wife died in the crash of a small airplane near Loreto. She was a nice person. On Christmas, she used to bring gifts for the children of the farmworkers. A year after his wife’s death, Kenny never returned; I’d lost a friend and a job I loved.

[3] Chollero comes from Cholla, the cactus with many small segments that detach easily and stick to anything passing nearby as a reproductive method. Baja California Cholla is not unique to Baja California Sur, but the name has come to stand for the 15% of its population that were born here and speak, or at least understand, the Chollero Spanish dialect.

Walking the Shore

With more time on his hands, Gringo started exploring the seashore with some of his pals. If they went by the tiny pueblo of La Ventana, they waved when they saw someone but never stopped to visit. Sometimes Guillermo made the four-hour hike to El Sargento alone to visit an aunt, his mom’s sister, who had recently married Esteban Lucero, a resident of the village.

On one occasion, a sixteen-year-old friend in El Sargento invited Guillermo to go deer hunting with him. They were hiking quietly in the foothills above the village when Guillermo stopped, put an index finger to his lips, and pointed to a dense grove of trees. He took a step forward, leaned over, picked up a rock, and threw it into the vegetation. A buck came charging out, and a loud BANG-BANG-BANG sent Guillermo sprawling. Then he heard his friend laugh and exclaim, ¡Lo tenemos! We got him! The boys took out their knives and began the bloody job of gutting the animal and dividing it into halves they could carry back to the village.

Fishing for Shark

In 1964, after turning 17, Guillermo moved in with his El Sargento aunt and uncle and started working as a fisherman for Raymundo Cosio, the brother of Victoriano who we met in an earlier chapter. Raymundo owned the village grocery store and all the boats and fishing tackle. He paid his fishermen half in cash for the catch and the rest in items from his store.

Juan Avilés made the fishing boats for Raymundo, and since electricity had not yet come to the village, Juan did all his work with hand tools. The first boats he made were heavy canoes. Later, he made pangas and even sloops, small single-masted sailboats.

Raymundo assigned Guillermo and Esteban’s brother, Eligio, to a canoe, Guillermo recalls.

Around 3 a.m. Monday morning, we started paddling to the island. When we got there five hours later, my shoulders and arms were screaming in pain, but it wasn’t long until I adapted and began to enjoy the rhythm of the sea and the firey-red sunrises. We thought we were brave going out as far as Cerralvo, but it was a picnic compared to the trips Salomé León, the founder of La Ventana, and his sons used to make. They paddled all the way across to the other side of the Sea of Cortéz to dive for pearl oysters.

After unloading our camping gear onto the beach, we threw a net just offshore to catch sardines, then used them to catch bigger fish that would attract sharks. We put the shark bait on a fifty-hook line called la siembra, the seed line, which was about 200 brazos, arms, in length with buoys at the ends and rock anchors attached to take it to the seafloor.

Show and Tell

After the siembras were in place, the men returned to the island to repair nets while they talked about everything under the sun. Some of the stories the fishermen told their children or landlubber friends back home were inspired by these bull sessions. One was about a wooden chest they found on a Cerralvo beach after a storm. It contained silver bars and Spanish flintlock pistols. The excited fishermen decided to leave the treasure on the island until they had a plan for divvying it up, so they buried the chest and returned home. In the meantime, another storm hit the island. When the fishermen returned, the shoreline had changed. They dug up a long stretch of beach, but never found the treasure. Then there’s the one about giant glowing orbs of light that sped away from Cerralvo’s shore underwater, broke the surface, and vanished silently into the night sky. Are there silver bars buried on Cerralvo and an alien UFO base beneath it, or is this what happens to your imagination after spending too much time at sea? [4]

After talking about his fishing days on the island with his buddies, Gringo leaned back and said,

Tomás, sometimes after a long day of work, we were so tired we just rolled out our blankets, lay back, and watched the stars come out. You wouldn’t believe how bright they get on a moonless night on Cerralvo. That’s where I learned stories like how the Milky Way formed when a goat herder took a container of sloshing milk to market in a burro-drawn cart. On the entire trip across the sky, it leaked, leaving the Via Láctea, the Milky Way, stretching across the heavens [5].

We sat quietly for several minutes. Then in a tone that seemed to drift back in time, Guillermo ended with,

Aquellos fueron los buenos viejos tiempos, Those were the good old times.

[4] To a young fisherman on his first trip to Cerralvo, a story such as The Legend of Mechudo might carry a warning: you never know what might be hiding just below the surface of the sea. This one originated during the heyday of pearling in La Paz when a crew of divers was sailing up the coast north of the city. After anchoring, Mechudo, the buzo, diver in command, checked the seafloor for pearl oysters. He surfaced and shouted that he’d found a giant pearl, but couldn’t extract it or the oyster. The other divers were eager to help but reminded Mechudo that the first pearl they found was for the church. Mechudo screamed no and dived to the bottom again. After several minutes, another person jumped in to check on Mechudo. When the second diver did not return, another volunteered. This continued until only one diver remained; he returned to La Paz with the terrifying story. In modern times, airplanes, boats, mine workers, and tourists have disappeared along the coast just above La Paz. If you go in that direction, don’t hike, camp, or anchor near Cape Mechudo.

[5]The Milky Way, Via Lactea in Spanish, is sometimes called the Camino de Santiago in Spain because pilgrims marching to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain follow its direction across the summer sky to reach their destination.

Photo courtesy of Sheldon Sails

Kite Surfing Instruction and Repairs

In La Ventana since 1997

All in a Day’s Work

On the island, the men awoke around 6 in the morning. If the coya, a strong northeasterly wind, were blowing, fishing would have to wait. After breakfast, they might play béisbol using a wad of socks for a ball and a piece of driftwood for a bat, or start a variation of horseshoes using sticks placed vertically into the sand about 10 meters apart and flat rocks in place of horseshoes.

When fair weather returned, the men pushed off for another day of work. Guillermo remembers one Friday in particular.

We landed a huge catch: rambusos, sardineros–magnificent animals–and hammerheads. We were grateful, but it was hard, dangerous work. When we got a shark next to the boat, we waited for a swell to help us lift it out of the water with gaffs and drop it into the bottom of the canoe. One mistake could cost a hand or an arm. Some of the sharks were 15 feet long and weighed more than 200 pounds.

My partner and I caught 52, and the other boats, something like 20 each. We cut the animal’s flesh into strips, salted and hung them on lines to dry, and paddled home. All weekend I thought about what I’d do with the money I’d get paid.

When we returned to the island on Monday, our dog started barking and running back and forth on the beach. We soon found out why; everything was gone! Fishermen from the mainland had motored across to the island and left with their pangas full of dried shark. We were angry. We didn’t get paid just for catching fish; we got paid for bringing back the fish we’d caught. We had no choice but to get back to work. Our luck soon changed; my partner and I had so many sharks we couldn’t load them all into the boat. We gave the extras to our friends, but not before cutting off the fins. You could sell a kilo of shark fins for nine pesos to buyers in La Paz for shipment to Japan. However, the entire catch belonged to Raymundo; he did give us a few extra pesos for the fins. Fortunately, the day would soon come when we didn’t have to work for Raymundo any longer.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Kahan

On the island, Guillermo met two brothers from La Ventana. They said they had a sister about his age named Josefa, and invited him to come by and meet their family. That was one of the luckiest days of his life.

Liza

The fishermen left El Sargento on Monday, September 27, 1976, crammed into a rattletrap pickup truck that had seen too many washboard mountain roads. They stopped in La Paz to pick up Guillermo’s brother, Alejandro, before driving out to Pichilingue, where they had left their co-op pangas. The sky was clear and the sea calm as they prepared for the trip to the fishing grounds off of Isla Espiritu Santo.

Silenced by the roar of outboard motors, Guillermo’s thoughts turned to Josefa and their two-year-old son, Jamie, back at home. The house Guillermo had helped build was a two-room structure with paraffin-impregnated cartón walls, a dirt floor, and a palm roof of dos aguas, two waters [6]. A few months earlier, electricity had reached their village. Josefa no longer had to light candles or kerosene lamps to illuminate the home’s interior. Someday, they hoped to buy a refrigerator and a few other luxuries, perhaps even a radio.

With his partner forward in the panga’s prow, Guillermo kept the speeding boat pointed towards Espiritu Santo. He chuckled to himself about the first time he met Josefa. She was milking a cow when he showed up at La Ventana to visit her brothers. He looked around and found an empty glass to use as an excuse to walk over and meet her. He handed the glass to Josefa and asked if she would fill it for him directly from the cow. She rolled her eyes, got up, and told him if he was thirsty, he could sit down and fill it himself. So Guillermo sat down and pulled on the cow’s teats but could not get a drop of milk. Josefa sat down again, squeezed a stream of milk into the pail, and told Guillermo to observe carefully how she did it. When he got his face near the cow’s udder, Josefa turned one teat so that a stream of the warm liquid hit him in the face; then she burst out laughing and continued milking. Guillermo got up slowly, surprised and a little embarrassed. However, it was love at first splat.

A sudden jolt brought Guillermo back to the present as the panga’s hull smacked against a higher swell. After landing on the island and setting up camp, the men headed back out to bait and anchor the siembras, then returned to the island. On Thursday morning, September 30, they broke camp and motored out to the buoys. The dark clouds billowing up in the south were a welcome sign that they might finally get relief from the arid summer and stifling temperatures.

A multi-year drought in Baja Sur had destroyed crops and cattle. Storms that usually brought rain had dissipated going out to sea. A late September tropical depression started on the same course, then turned north. The day after the fishermen landed on Espiritu Santo, it had exploded into Hurricane Liza with winds over 140 mph. Now it was churning up the Gulf at record speed, flooding coastal villages along the way.

Around midmorning, Guillermo noticed that other fishermen were starting to return to La Paz. When a panga passed nearby, someone shouted, Huracán! The men pulled in their lines and weighed anchor. Jose Luís decided to go back to the island where Josefa’s cousin was fishing and would probably take shelter in a cave they were both familiar with.

Guillermo was a seasoned mariner. He had navigated canoes and pangas through heavy seas before, but he remembers things were different this time:

Rain began to fall, and the wind started to howl. We were caught off guard by the sudden onset and ferocity of the storm. I struggled to keep the panga from capsizing as the gale lifted us up to the crest of a wave and then slammed us down the other side where it was all I could do to keep from broaching. The rain stung my face and hands as I struggled to steady the vessel. I lost sight of the other boats and realized that if we capsized, there would be no one to rescue us. It crossed my mind that this was how fishermen disappeared.

[6] Un techo de dos aguas, a roof of two waters, is what English describes as a gable roof, one that slopes away from the center ridge in opposite directions (carrying rain runoff away as “two waters”).

Danger

Josefa and her neighbors watched the dark clouds growing in the south and hoped that rain would soon end the drought and turn the desert vegetation green again. When the storm arrived, its intensity caught everyone by surprise. Although its eye was 50 miles away in the middle of the gulf, strong wind and rain were already battering their vulnerable homes. Josefa heard screams as the roof of a nearby house ripped off and crashed through the village. She held Jamie tighter and prayed that Guillermo, her cousin, and the other fishermen were safe on land. A growling gust of wind clawed at the roof and ripped a section off. There was a sudden rumble: a wall of water and rock from the heavy rainfall in the mountains was roaring down the nearby arroyo.

Death and Destruction

After struggling for almost three hours with the angry sea, the El Sargento men landed their pangas back at Pichilingue and went to stay with relatives in La Paz. Just a few blocks from where they spent the night, thousands of people died when a levee above the city broke, and a wall of water crashed through the western edge of town and carried away cars, homes, and their occupants. The next day, when the fishermen saw the death and destruction that Liza had inflicted on La Paz, they left for home.

As they made their way back to El Sargento over a muddy road full of new potholes and washouts, no one spoke of their shared concern: had their pueblo and families survived. When the pickup got mired in mud partway down the long grade overlooking Los Planes, they abandoned it and made their way home on foot. Fortunately, everyone there had survived, but there was a lot of work to do to repair the damage to their village.

Eligio’s brother, Jose Luis, survived the night in the cave on Espiritu Santo, and the next day he motored home. Years later, he opened a small store next to the baseball field in El Sargento. Josefa’s cousin never made it to the cave. Neither he nor his boat was ever found, and several Japanese fishing vessels and their crews also disappeared.

Josefa

Twenty years later, Josefa started selling homemade tamales in the same campground where her pearl-diver grandfather had founded La Ventana, and she had grown up. Guillermo began working for foreigners who were building homes in La Ventana. Sometimes he explained to them the meaning of a Spanish word or phrase used by a Chollero worker from a mountain rancho. After all, Guillermo had worked for Kenny, and his nickname was still Gringo.

Tom at BajaNightSky@gmail.com