Read Part 1 of this story first, if you haven’t already. Onward…

The crew was anxious to port in La Paz. Their encounter with ragged little St. Lucas had been disappointing.

Cape St. Lucas had not really been a town, and our crew had convinced itself that it had been a very long time out of touch with civilization…. In addition, there is a genuine fascination with of the city of La Paz. Everyone in the area knows the greatness of La Paz. You can get anything in the world there… (and) a cloud of delight hangs over the distant city from the time when it was the great pearl center of the world.

Steinbeck noted that the La Paz pearl oyster drew men from all over the world.

And, as in all concentrations of natural wealth, the terrors of greed were let loose on the city again and again.

In Chapter 11, he recounts a cautionary folk tale about the greed associated with finding a massive pearl. The story became the catalyst for his novella, The Pearl, published in 1945, in which an impoverished pearl diver finds a huge pearl. “The Pearl of the World” promises to transform his life. It does, but not in the way one might expect.

By 1936, a century of rampant overfishing of oyster beds had depleted natural stocks to the point where recovery was unlikely. To cap it off, an unknown disease then spread rapidly through the remaining oysters, virtually wiping them out. By the time Steinbeck arrived, the glory days of Mexican pearling were over.

During several days of collecting, the crew was joined by a rag-tag rabble of young boys seeking adventure. Steinbeck rewarded them with 10 centavo pieces for specimens they collected. Even if creatures captured by these budding marine biologists were too mangled to be useful, Steinbeck paid them anyway.

On departure early on March 23, Steinbeck pondered:

We wondered why so much of the gulf was familiar to us, why this town had a ‘home’ feeling. We had never seen a town which even looked like La Paz, and yet coming to it was like returning rather than visiting. Some quality there is in the Gulf that trips a trigger of recognition so that in that fantastic and exotic scenery one finds oneself nodding and saying inwardly, ‘Yes, I know.’

What followed were many collecting stops as the Western Flyer motored up the ever-fascinating coast—San José Island, Puerto Escondido and Loreto.

We were eager to see (Loreto), for it was the first successful settlement on the peninsula (1697), and its church is the oldest mission of all. Here the inhospitality of Lower California had finally been conquered and a colony had taken root in the face of hunger and mishap.

The crew visited the tumbled-down mission.

The Virgin Herself, Our Lady of Loreto, was in a glass case and surrounded by the lilies of the recently passed Easter. In the dim light of the chapel she seemed very lovely. Perhaps she is gaudy (but) she has not the look of smug virginity so many have—the ‘I-am-the-Mother-of-Christ’ look—but rather there was a look of terror in her face, of the Virgin Mother of the world and the prayers of so many people heavy on her.

After several collection stops, the expedition motored into the deep pocket of Concepción Bay, forgoing the opportunity to visit Mulegé.

We had no plan for stopping there, for the story is that the port charges are mischievous and ruinous…. Also there may be malaria….

The northward journey continued past French-flavored Santa Rosalia. The French company El Boleo founded the town in 1884 and exploited copper mines there until they closed in 1954. The company built houses and installed the metallic Iglesia de Santa Bárbara, which is said to have been designed by Gustave Eiffel in 1897. (wikipedia)

Perhaps the most spectacular scenery encountered in the Upper Gulf proved to be Bahía de Los Ángeles. The 25-square mile bay is surrounded by 15 islands.

The Coast Pilot had not mentioned any settlement, but here there were new buildings, screened and modern, and on a tiny airfield a plane sat. It was an odd feeling, for we had been a long time without seeing anything modern. Our feeling was more of resentment than of pleasure.

The expedition now turned its attention to the mainland coast of the Gulf, crossing just above the massive Tiburon Island, bound for the mainland city of Guaymas.

Arriving in Guaymas on April 5, Steinbeck noted:

At La Paz and Loreto, the Gulf and the town were one, inextricably bound together, but here at Guaymas, the railroad and the hotel had broken open that relationship…Guaymas seems to be outside the boundaries of the Gulf.

On route to a few remaining collection points before the Western Flyer would need to motor quickly back to Monterey at the end of its charter, Steinbeck and crew encountered the Japanese shrimping fleet, consisting of a 10,000-ton mother ship and 11 dredge boats of 150-175 feet.

They were doing a very systematic job, not only of taking every shrimp from the bottom, but every other living thing as well. They cruised slowly along in echelon with overlapping dredges, literally scraping the bottom clean.

Steinbeck would be dismayed to learn that fishing practices such as this continue today. Many marine ecologists doubt the Gulf, famously dubbed “The Aquarium of the World” by Jacque Cousteau, can continue to sustain it rich biodiversity. The Gulf is home to 950 species of fish, 100 of which are found nowhere else. The world’s most endangered marine mammal, a small porpoise called vaquita, lives in the Upper Gulf. At present, only 7% of the Gulf is protected and 0.5% is devoted to “no take” zones.

(Author’s Note: from Edible Baja Arizona “In the 1940s, shrimp trawling emerged; foreign fleets maneuvered up the Gulf with bottom trawlers in their wake, scraping up eight inches of ocean floor to find just one fish. The bycatch rate for these trawlers continues to hover around 85 percent—that is, for every 100 pounds of seafood caught, 85 of it is left on a boat deck to die. Virtually all the Gulf’s sandy bottoms have now been dredged by Japanese and Korean trawlers….” )

As the Western Flyer rounded the Cape,

…a crazy literary thing happened…there was one great clap of thunder, and immediately we hit the great swells of the Pacific and the wind freshened against us. The water took on a gray tone….

The real picture of how it had been there and how we had been there was in our minds, bright with sun and wet with sea water…. Here was no service to science, no naming of unknown animals, but rather—we simply liked it. We liked it very much. The brown Indians and the gardens of the sea, and the beer and the work, they were all one thing and we were that one thing too.

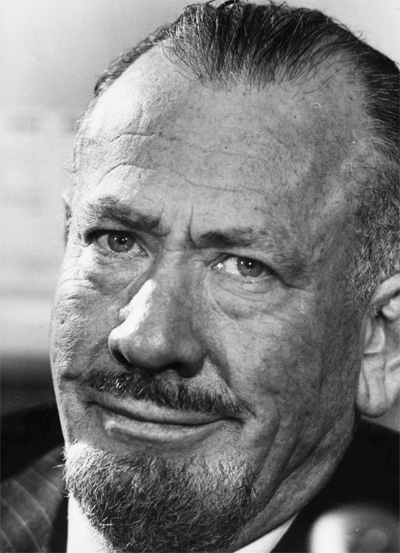

John Steinbeck was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1962. He died in 1968 at age 66.

Details about Lorin’s two recent books—The 13: Ashi-niswi (2018) and Tales from The Warming (2017)—are available at lorinwords.com