From El Sargento and La Ventana, you can watch shadows paint Isla Cerralvo a changing hew of colors from sunrise to sunset. The island provides beautiful views, but it also conceals many tales. The Caballera de Cerralvo, told here for the first time, is one of them.

Isla Cerralvo

In 1930, ornithologist Griffing Bancroft and his wife, former silent movie actress Margaret Wood, joined other naturalists on a five-month voyage to explore the Baja California coastline and document its bird and animal life. Griffing published an account of the journey in The Flight of the Least Petrel, where he called Cerralvo Island an unwatered, ugly mass of ash and lava, whose fauna others had described so well that he felt no obligation to go ashore.[1]

Bancroft’s “ugly mass of ash and lava” had been a Pericú Indian refuge for millennia. Their 1734 revolt against Jesuit intruders left several priests dead in La Paz and the Cape Region. The attackers escaped to Cerralvo by raft and disappeared safely into the island’s interior.

Two hundred years earlier, Cortez had anchored his ship at the island’s south end after a yardarm fell during a storm and killed the pilot. The crew buried the poor man on the island, repaired the vessel, and replenished its fresh-water supply from an arroyo. Before weighing anchor, Cortez named the island Santiago after Spain’s patron saint. A century later, Francisco de Ortega anchored off the island’s western shore and renamed it Cerralvo to honor the Viceroy of Mexico, the 3rd Marques de Cerralvo, who had approved the voyage of exploration.

In 1899, pearl diver Antonio Ruffo acquired a concession to farm and harvest pearls on Cerralvo and set up his operation in the Paredones Arroyo. Two great-grandfathers of dozens of young people in La Ventana made the voyage from La Paz to Cerralvo many times in the 1920s and 30s. Juanito Lucero managed the Cerralvo Ranch for the Ruffos. Each week he would sail a chalupine, a small boat with a large sail, to La Paz, load it with supplies, and navigate back to the island.[2] Salome León, the founder of La Ventana, worked for the Ruffos as a pearl diver until he could afford to buy diving equipment.

La Caballera de Cerralvo

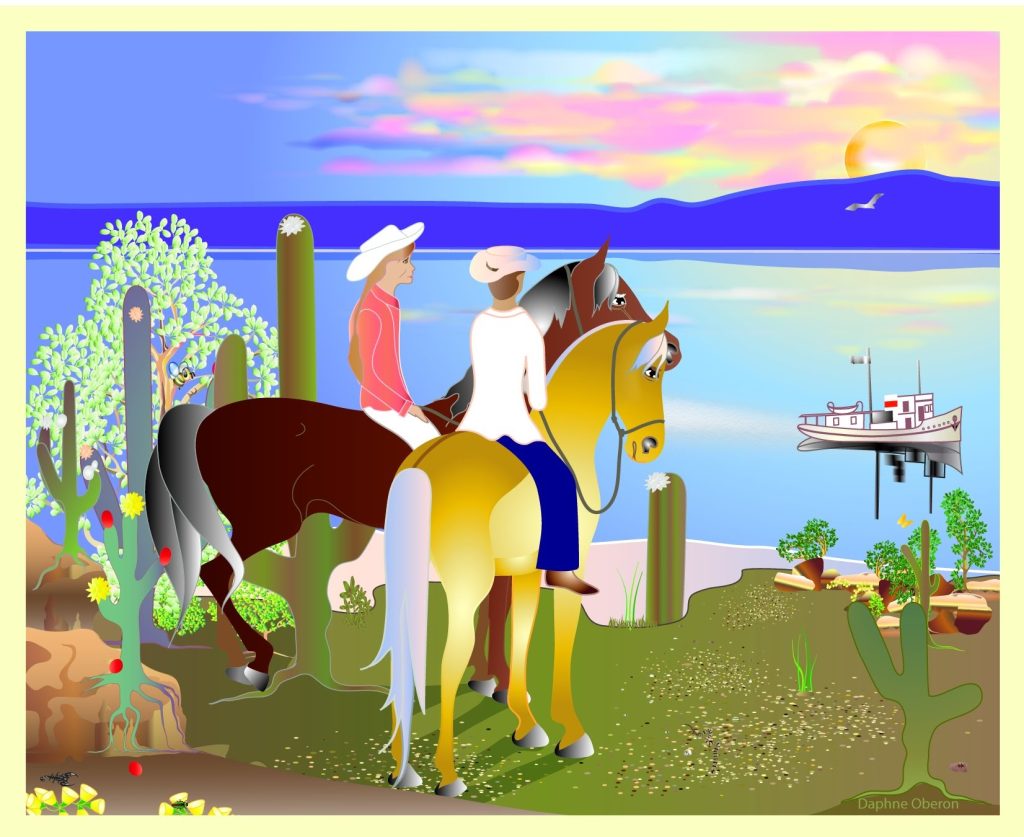

One day in 1966, El Sargento fishermen camping on the island were astonished to see a young girl with long flowing hair riding a horse bareback on the beach near their campsite. They called her La Caballera de Cerralvo, the horsewoman of Cerralvo. Her name was Daphne.

Daphne explored Baja California on horseback with her father, Englishman Dr. David Burden. Starting in the late 1950s, when she was four, she rode behind him on the saddle skirts to mountain pueblos and ranchos west of their base camp in San Bartolo. While her eccentric father provided medical services to ranch hands, Daphne picked up their Chollero Spanish dialect passed down by their ancestors. Motivated by necessity and passion, she soon handled Baja ponies and burros like an expert.

Daphne recognized that her father was less concerned for her welfare than the people he provided medical care. He seemed to believe it was God’s responsibility to look after her, not his. His attitude had led to her infant sister drowning in California while left unattended, a death her father failed to report to the authorities.

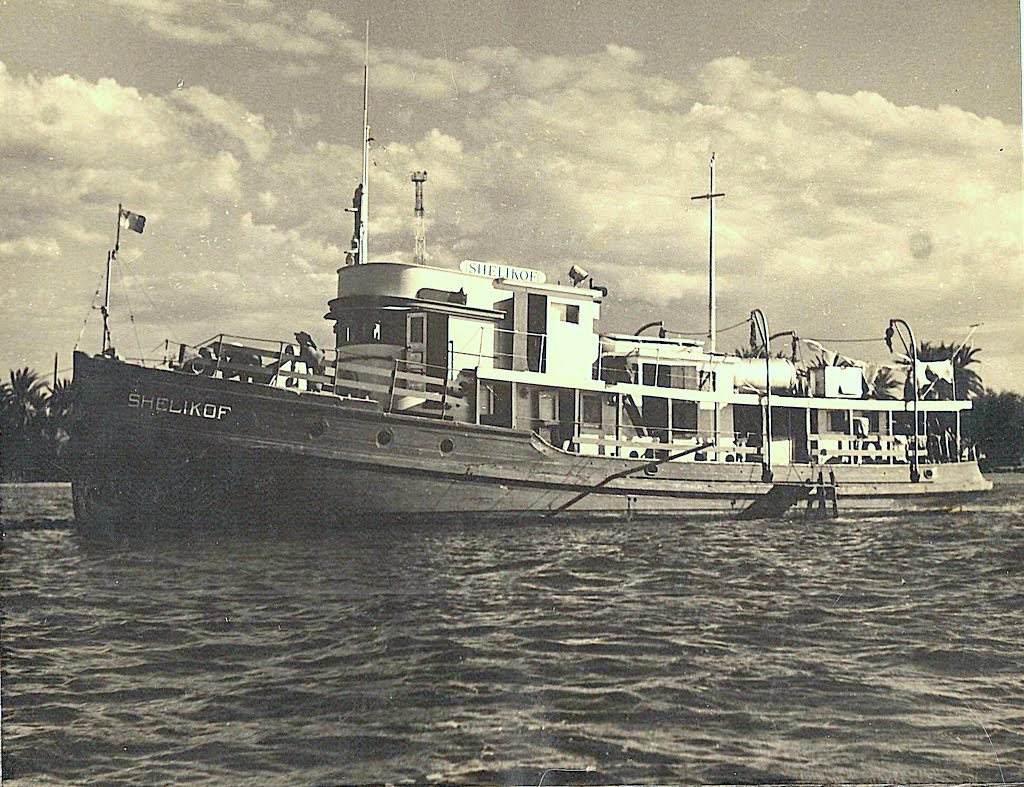

The Burdens conducted their Young Pioneers School in San Bartolo from 1959 to 1963.[3] In 1964, they moved the school to a converted ocean-going tugboat, the Shelikof, which they anchored off El Cardonal, a pueblo thirty-some miles south of La Ventana.

In 1966, when Daphne was 13, the Burdens leased Cerralvo from Tony Ruffo, Antonio Ruffo’s grandson. Dr. Burden transported horses, donkeys, and goats to the abandoned Paredones ranch site, which had a bitter mineral water well. On November 1, the boat, renamed the Forge, left El Cardonal for the last time, and a few hours later, Daphne and her mom disembarked at the Paredones beach. They unloaded army tents, tools, and enough supplies to last the winter. There are no protected anchorages on Cerralvo; whenever a chubasco, huracán, or el norte threatened, Dr. Burden took the tugboat back to La Paz, sometimes for several months at a time, leaving his frail wife and Daphne to fend for themselves.

In late spring the following year, Daphne loaded tents, tools, and supplies onto burros and moved their camp four miles up Las Delicias, the next large arroyo to the south. Daphne directed Mexican workers from El Sargento, who helped her dig a well, build a coyote-fence goat corral, and move a large ramada from Paredones to the Las Delicias beach.

A plague of wasps forced Virginia to leave the island and live aboard the Forge. Daphne was happy to stay on Cerralvo alone. She explored the island on horseback and came upon bighorn sheep that did not fear her or the “sportsmen” from La Paz who hunted the magnificent animals. The remaining bighorns were all killed within three years.

Visiting El Sargento

When Virginia wanted to return to her house at Rancho San Martin, Dr. Burden took the Forge across the bay to El Sargento to purchase needed supplies and drop his wife off to wait for a taxi from La Paz. Daphne went along to plead for more animals to use on the island.

“We went ashore, and my father talked to Raymundo, the portly El Sargento gentleman who sold provisions to community members. He procured the supplies my father needed,” Daphne recalls. “Raymundo pointed to a large, grey jack burro that squealed and gnashed its teeth at other burros in a garbage pit behind Raymundo’s store. Raymundo wanted twenty pesos for the big nuisance burro, one of the jennys, and a day’s wages for his men to round them up and load them onto the boat.

“If the kids crowding around who called Raymundo papa were any indication, he must have had a mistress or two. My father would know. As a doctor, he was like a father confessor, and women seemed to take comfort in telling him the most personal secrets about their families.[4]

“While my parents speculated about Raymundo, I slipped away to oversee loading the animals we had bought aboard a launch my father had built for this purpose. I had a big job cut out for myself taming that ornery donkey.”

Hunger Games

Besides rice and canned tomato sauce, doctor Burden left his daughter with little food. “I had no choice but to forage for the island’s edible plants,” Daphne told me. “I dug up starchy San Miguel tubers and gathered purslane, nopal pads, figs, and cactus fruit. Sometimes I felt like I burned more calories gathering food for myself than the calories it provided.[5] I was also on the lookout for feed for our animals. I piled bushels of thorny uña de gato and a trumpet-flower vine called yuca on the back of a donkey to take to the horses.”

Daphne had thought about riding to Cerralvo’s White Mountain peak from her arroyo camp to check out the view. She decided to attempt the northeast ridge, which was steep and covered with loose shale. “Sometimes, I had to race my pony forward to outrun the landslides we kicked up. Just before the summit, I made a serendipitous discovery—the tallest amaranth I’d ever seen, growing in a large pool of water. I collected a bushel of the plant’s nutritious and tasty leaves, stems, and seeds to take back to camp.”[6]

A Butcher Turned Surgeon

One day, Daphne discovered a gentleman camped in a nearby arroyo. He was a retired butcher from La Paz named Manuel, tall and quiet and wearing tire sandals on his weather-worn feet. “I learned a lot from this wilderness man. He had carved bowls and other useful things for his camp and taught me how he caught and prepared lizards, iguanas, snakes, and birds for a meal. While my diet was mostly vegetarian, in a pinch, I could use this information.”

Dr. Burden had imported some big buck goats, and one time Daphne got on the wrong side of one of the beasts. It butted her over a cliff into a giant cardón. “I hung impaled by my arms, screaming my head off. Manuel heard my cries for help, came to my rescue, and got me down. He carried me back to his camp and helped me remove the shirt nailed to my body by cardón thorns. Manuel pinched my skin to make the broken spines protrude enough to pull them out with tweezers he made from heavy wire pounded with a stone to flatten the ends. The old butcher sharpened a knife and made fine incisions in my flesh with a surgeon’s skill to get at deeper pieces. Blood was everywhere, making it challenging to find the painful spiny splinters. I was a mess, but he treated me like his granddaughter and probably saved my life. We kept that whole episode a secret between us.”

Dana

In 1967, Dr. Burden sent nine-year-old Dana Coates to keep Daphne company on the island as the lad did not like living on the Forge. Whenever the tugboat returned from El Sargento or La Paz with fresh supplies, the duo rode down to get the latest news and returned to camp with a bag of vegetables. “One of us would remove the thorns and fibrous material from a spiny Cerralvo nopal cactus pad. We’d prepare a favorite meal of nopal, onions, and potatoes, sautéed in tomato sauce,” Daphne recalled.

Esteban Lucero

Esteban and Pepe Lucero were the El Sargento brothers Dr. Burden had hired to help Daphne dig the Delicias well and build trails across the island. Daphne told me that Esteban was a kind man and a great storyteller. “The tales about his father flavored the magical portrayal of Don Tomás in my first Baja California Sur novel, My Grandfather’s Horses.[7] Dana was younger and more impressionable than I was. He learned a lot when Esteban told us stories about growing up and the area folklore—like the ghosts of pearl divers and the mysterious moving orbs of light sighted along the Gulf and island shores.”

Earthquake

One afternoon in 1969, while Dana was preparing dinner, Daphne hiked up a ridge looking for the goats. To get a better view, she climbed a tall Torote Colorado, the “elephant tree” that gives off a turpentine smell and grows taller on the island than on the peninsula. She was high up in the tree when the ground began to roll and shake. The tree reacted by catapulting her toward the edge of the ridge. Only an ironwood thicket stopped her fall, the thorns tearing her skin. She described what happened next: “I picked myself up but could hardly see my hands since the quake had kicked up so much dust that it soon covered the sun. As Cerralvo shuddered as a ship ran aground, slabs of slate broke off from the mountain ridges causing avalanches of earth and boulders that roared and echoed off arroyo walls like thunder.”[8]

Daphne returned to her camp safely, but an aftershock caused the well to dry up. She and Dana only had enough drinking water for a few days, and Daphne’s father had taken the school tugboat back to La Paz. The horses were soon dehydrated and unsteady, hanging around the well and braying for water.

Because of foul weather, the two youths could not count on help from their El Sargento friends. “We had no choice but to bring back bitter water for the animals from the Paredones well,” Daphne remembers. “I started thinking about how to launch the old boat that sat high on the Delicias beach. It was a large panga that required a high tide for launching. A storm was coming from the south along with the incoming tide, so the wind and current would help us, but we might need more than a couple of broken paddles to travel two miles north to Paredones. I made a grappling device from shark fishhooks and a heavy line beside our beach ramada. I could throw it before the boat to pull us forward when it caught on the seafloor.”

Daphne and Dana loaded the boat with empty water containers and some food and managed to launch on an outgoing high tide. When they got to Paredones, they found one horse near death and the others in bad shape.

“After boiling water from the Paredones well for ourselves, we began filling containers and loading them onto the panga,” Daphne recalled. “The next morning, we launched on a tide flowing out of the Gulf toward the Cape. As it carried us back to Delicias, we drifted farther away from land. I screamed at Dana to pull harder, but the current’s grip began to take us into the dreaded Cerralvo Channel and out to sea. I caught Dana’s eye and nodded towards the shore. He understood. We must abandon our life-saving water cargo and swim for the beach.”

To Be Continued…

Footnotes

- The book’s complete title is Lower California: A Cruise; The Flight of the Least Petrel, online at here. Use the slider at the bottom of the page to find pp. 180 and 181 for Bancroft’s complete description of Cerralvo. There are excellent descriptions of Baja California life in the early 1930s.

- Herp.mx is a beautiful website featuring this writeup on the snakes of Cerralvo, including the endemic Cerralvo Island Rattlesnake. It also mentions the date Antonio Ruffo began his operation on Cerralvo. Two great-grandfathers of dozens of young people in La Ventana made the voyage from La Paz to Cerralvo many times in the 1920s and 30s. Salome León, the founder of La Ventana, worked for the Ruffos as a pearl diver until he could afford to buy diving equipment. Juanito Lucero managed the Cerralvo Ranch for the Ruffos. Each week he would sail a chalupine, a small boat with a large sail, to La Paz, load it with supplies, and navigate back to the island.

- Daphne’s mother, Virginia, had studied philosophy and authored a book, The Process of Intuition. Before the Second World War, she worked as an accomplished stage actress and tutored later Hollywood greats like admirer David Dortort, producer of Bonanza, in the art of oratory. She managed Veteran and Red Cross hospital programs during the war.

- Dr. Burden had previously dealt with situations like this; the worst example was at El Cardonal. Daphne described this in our correspondence: “There were no roads to the tiny pueblo in those days, and women who stayed home had no interaction with the outside world. The male head of a large family had fathered several of his pre-teenage daughters’ babies. The man’s legal wife looked three times her age and had a large, dangling nose. Stressed out from keeping her husband away from their children, she was grateful to have a listener in my father. He was pulling his hair out, wondering what to do. Maybe this was one reason my father rounded up a work crew and built the first road that connected El Cardonal to its nearest neighbor.”

- The San Miguel or Coral Vine is sometimes called wild Bougainvillea but is part of the begonia family. In their Baja California Plant Field Guide, 3rd edition (page 345), Rebman and Roberts write that Indigenous People used both seed pods and underground tubers for food.

- Over the next five decades, weathering from wind, earthquakes, and hurricanes filled in White Mountain’s crater and rounded off the top of the mountain, much like Cerro Colorado, the rose-colored volcanic dome that looms up behind the hilltops to White Mountain’s southeast.

- The date of the earthquake is uncertain. There were two earthquakes just hours apart in August 1969. Some people in El Sargento reported an earthquake in April of that year.