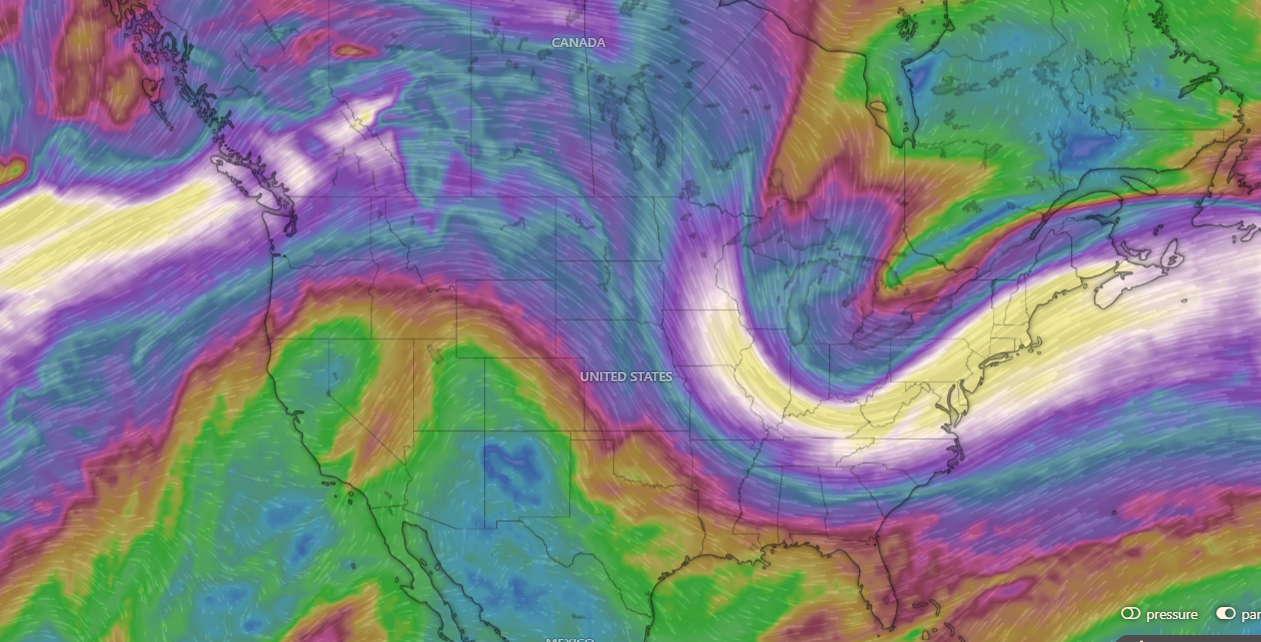

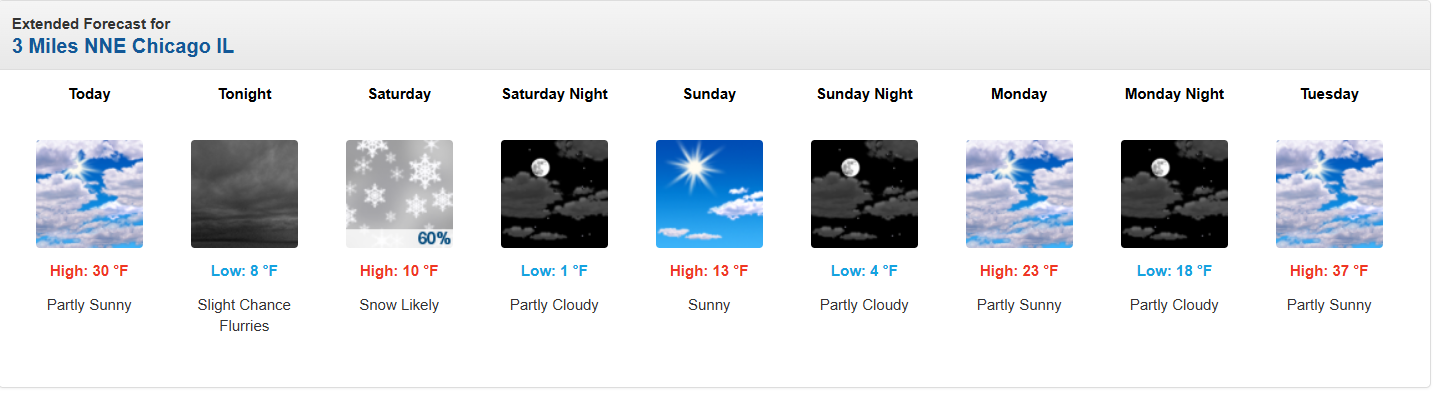

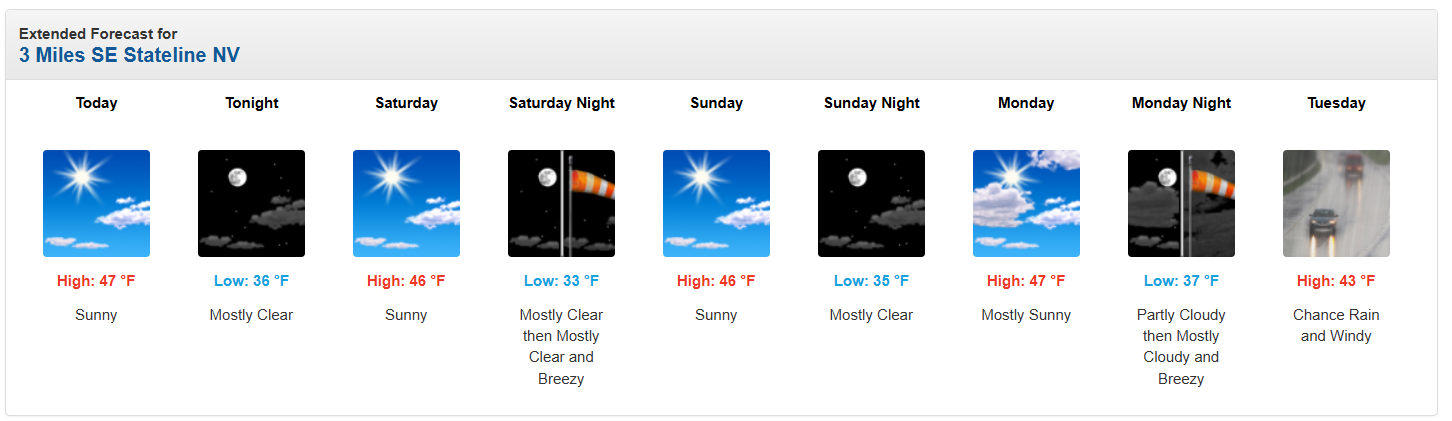

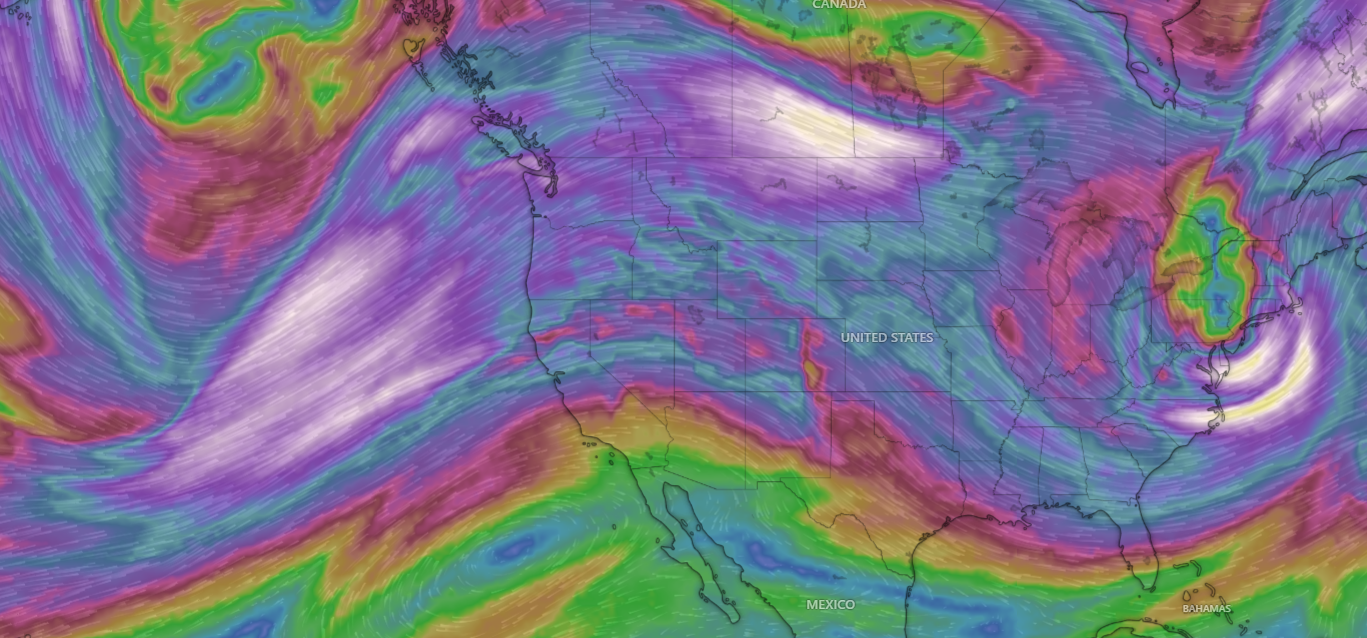

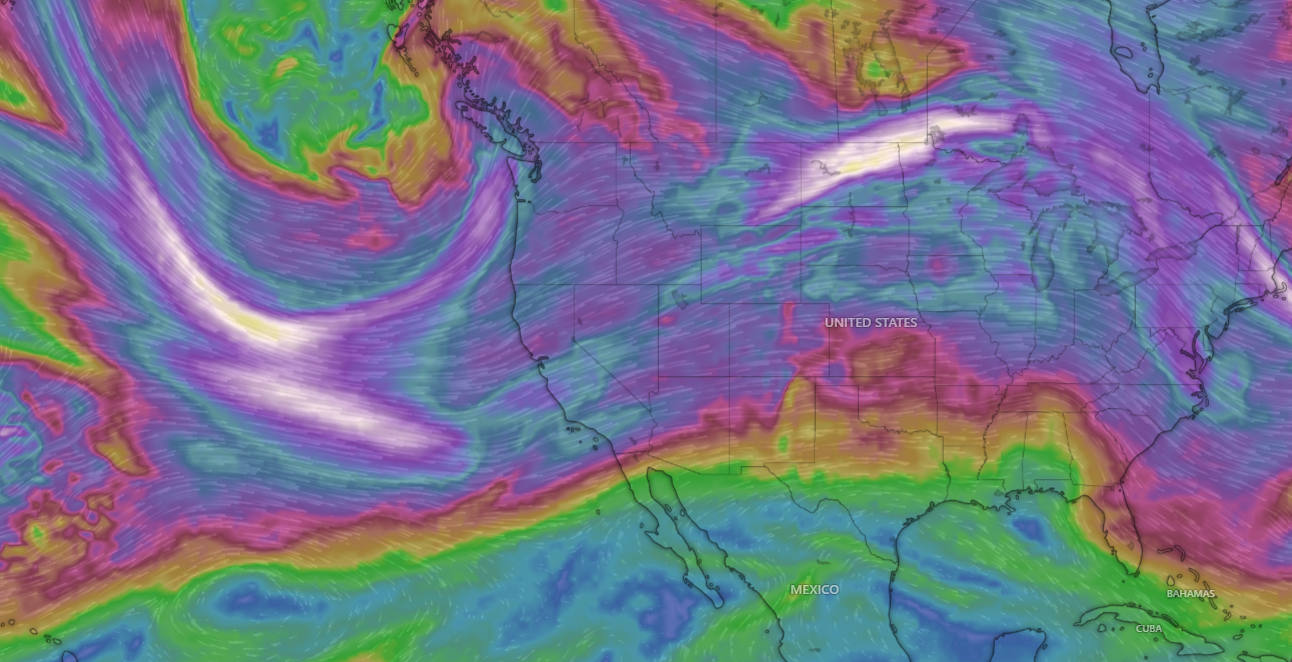

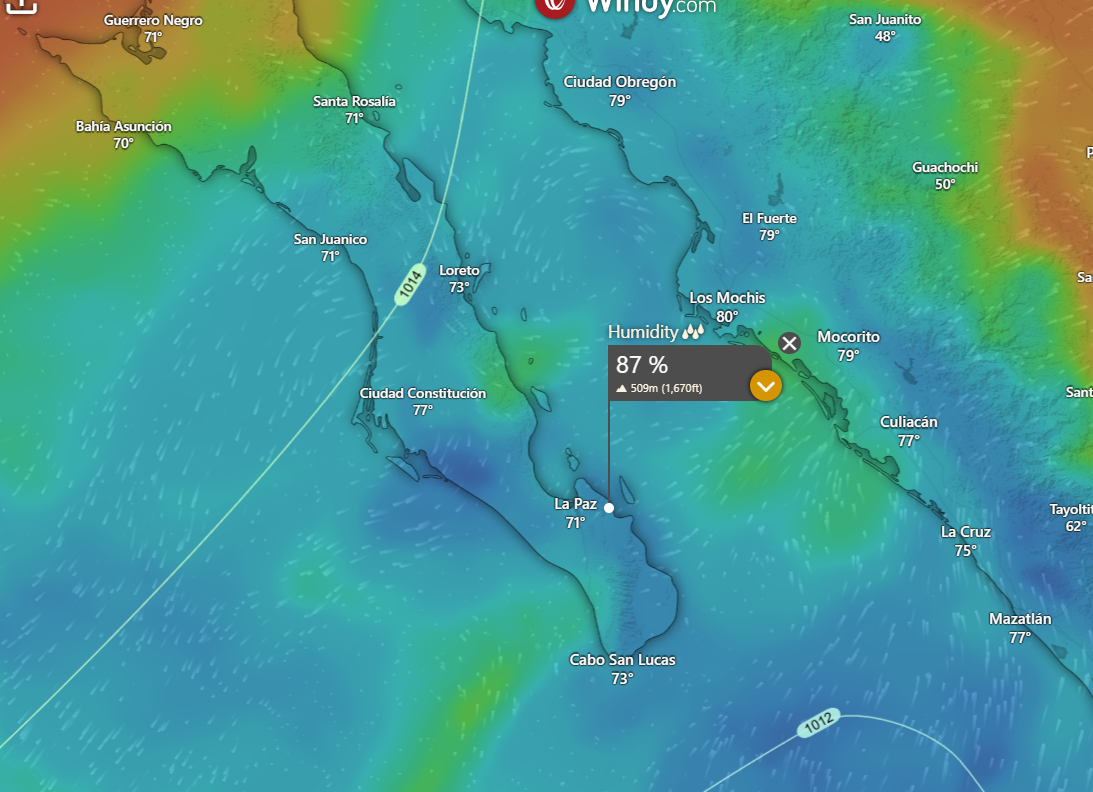

¡Buenos dias! There were no passes by the polar-orbiting satellites last evening so we'll have to go solely with model predictions of winds today. The good news it that all of the latest numerical model forecasts show a continuation of solid NNW background wind through Wednesday, as the surface high pressure system to our north holds firm. The wild card for today will be the thickness of high clouds. Infrared satellite loops early this morning showed a narrow but substantial band of high clouds approaching our area from the west, but several of the models show the thickest clouds will remain just to our northwest, with substantial filtered sun here this afternoon. Another reason to be optimistic for today is that several of the models show a slight increase in background flow this afternoon. Although some high clouds will likely remain on Monday, we should see ample filtered sunshine to once again trigger our wind machine. Full sunshine is forecast for Tuesday and Wednesday, and with solid NNW background flow, we should see our streak of windy days continue. Long-range model forecasts are in good agreement that the surface pressure gradient will become weak on Thursday, with a down day likely. We might see a slight increase in winds on Friday, but very light winds will likely return again on Saturday.

(Tides)- Today…High clouds this morning, then becoming mostly sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Monday…Mostly sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Tuesday…Sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Wednesday…Sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Thursday…Sunny. Northeast wind 10-12 mph.

- Friday…Sunny. North wind 14-16 mph.

- Saturday…Sunny. Northeast wind 10-12 mph.