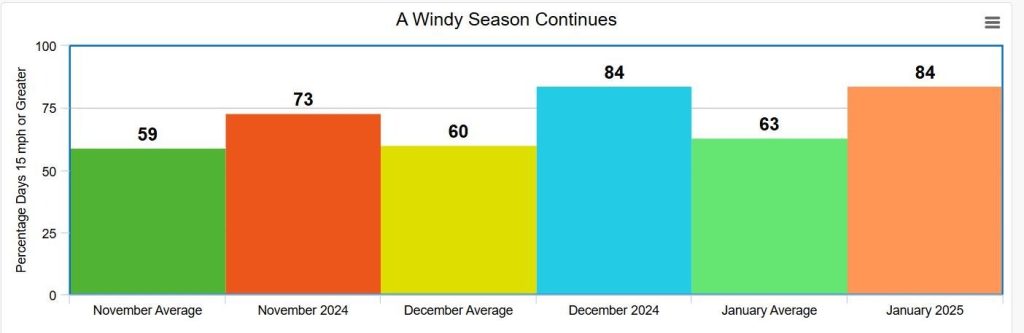

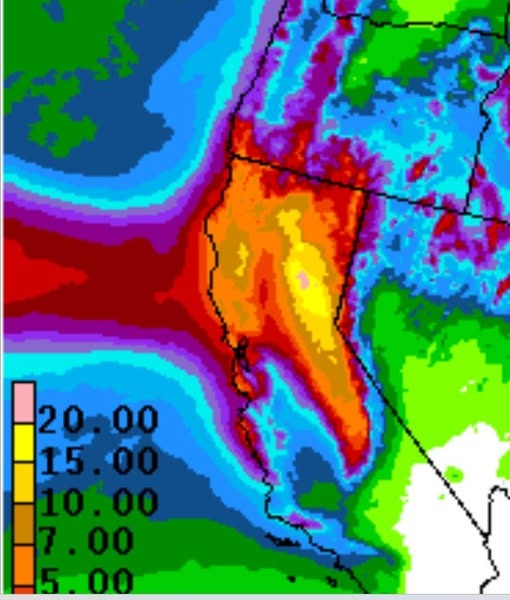

¡Buenos dias! An ASCAT satellite pass last evening measured WNW winds of 5 to 10 knots over the Sea of Cortez just east of Cerralvo, and model forecasts show the background flow will likely be just below the lower threshold for fully triggering our local wind machine today. Infrared satellite loops early this morning showed an area of thin, high clouds streaming into BCS from the west, and these will likely partially dampen our local thermal as well. That said, it’ll be very close, and the High Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model shows marginally kiteable wind (12-14 mph?) along the northern beaches for a couple of hours early this afternoon. Model forecasts are in excellent agreement that we will see very light background flow on Tuesday, with only light onshore breezes expected. The forecast for Wednesday and Thursday remains a low-confidence one, as the models show the background flow will be very near the threshold we need for kiteable winds, but at this point I will continue to be optimistic. Sunny skies will be in our favor both days, so if we are lucky we may see things come together. The latest model runs are in good agreement that surface high pressure over the eastern Pacific will build into BCS on Friday and increase the north flow over our area. At this point it looks like solid north flow will continue through next weekend, and with sunny skies expected, we should see good thermal boosts each day. Looking farther into the future, both the European and American long-range forecasts show a favorable weather pattern setting up for sufficient north flow into the middle of February, so our AMAZING 2024-25 season looks like it may continue (see graph below).

- Today…Mostly sunny. Northeast wind 10-12 mph.

- Tuesday…Mostly sunny. East wind 8-10 mph.

- Wednesday…Sunny. Northeast wind 16-18 mph.

- Thursday…Sunny. North wind 16-18 mph.

- Friday…Sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Saturday…Sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Sunday…Sunny. North wind 18-22 mph.