A Reminder For Fellow Kiters This Weekend… With the local beaches filling with folks enjoying the Semana Santa weekend, it’s important for those of us also using the beaches to kite to be extra careful, particularly when launching and landing our kites. There will be many people, especially children, who are unaware of the potential dangers so please be particularly mindful of your surroundings this weekend. Thank you and Happy Easter!

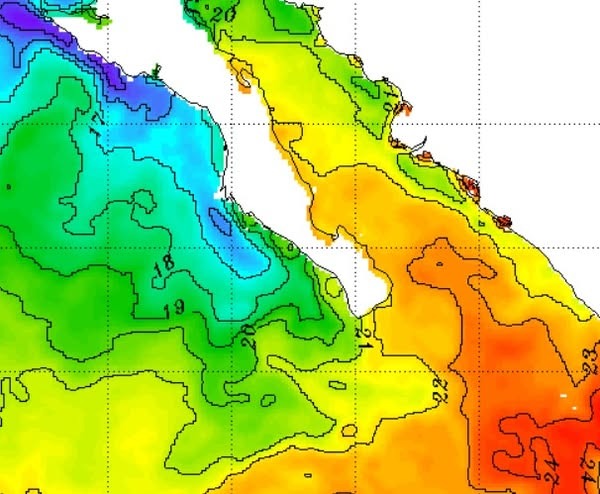

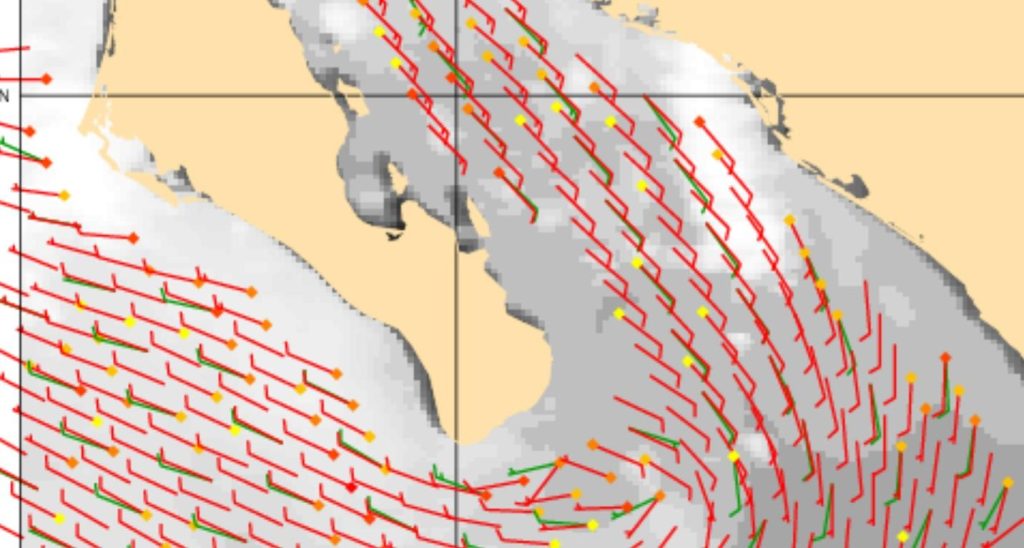

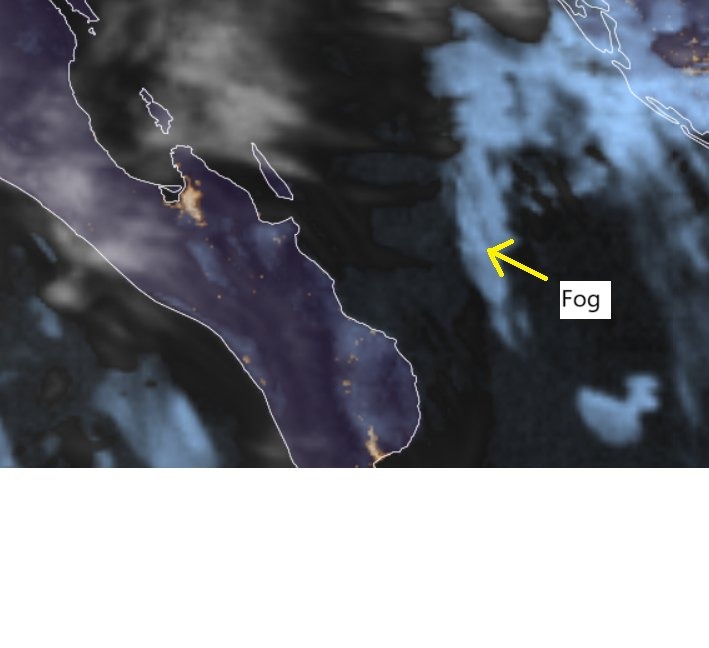

¡Buenos dias! A pass just after midnight of the Oceansat satellite measured NW winds of 5-10 knots just east of Cerralvo, and model forecasts show solid north background flow for today. Infrared satellite loops show an area of high clouds lurking just to our west, and model forecasts indicate that we will likely see significant high cloud cover moving in later this morning. There are some indications that we will see a few thin spots in the cloud cover, so there should be enough filtered sunshine to trigger at least a partial thermal boost. Model forecasts are in good agreement that sufficient north flow will continue through the remainder of the Semana Santa weekend, and with sunny skies expected, we should see our local wind machine in fine form. Longer range forecasts start to disagree around Monday, but at this stage it looks most likely that we will see at least one more rideable day. Tuesday will likely be a transition day into a light wind regime on Wednesday.

- Today…Partly sunny. North wind 16-18 mph.

- Saturday…Sunny. North wind 16-20 mph.

- Sunday…Sunny. North wind 18-22 mph.

- Monday…Sunny. North wind 16-18 mph.

- Tuesday…Mostly sunny. North wind 14-16 mph.

- Wednesday…Mostly sunny. East wind 8-10 mph.

- Thursday…Mostly sunny. East wind 8-10 mph.