Since the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519, Mexico has gone through several major political iterations. But La Paz and the Peninsula have, in addition, had their own peculiar brushes with international politics. First, some early history.

La Paz Bay was “discovered” in 1533 by Spaniard Fortun Ximenez, but efforts to establish a colony were thwarted by natives who killed him and his 21 crew members. Hernán Cortez arrived in 1535 after successfully subduing the mainland and named the Bay “Santa Cruz.” But his attempt to gain a foothold on the wild Baja peninsula also came to naught. His colony failed in a few years.

Fast forward to 1596 when the Spanish finally made a go of it. A successful colony was founded by Sebastian Vizcaíno and given the name “La Paz.” “New Spain,” as the country was known, held forth until 1821 when, after a protracted struggle (1810-21), the sovereign Republic of Mexico was established with the signing of the Treaty of Córdoba.

In 1861, however, conservative elements fought for the return of a monarchy. The French helped make it happen. France invaded and put monarch Maximillian I on a throne. The U.S. during this period, of course, was embroiled in the Civil War and didn’t have resources to help Mexican liberals keep the French out.

But, at the end of the war, the U.S. actively opposed Maximilian’s regime. France withdrew its support in 1867, monarchist-rule collapsed, Maximilian was executed, and the republic was restored.

While all these milestones were of great importance to the nation as a whole, La Paz, Baja and what is now the State of Sonora—on the heels of The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848)—were embroiled in 1854 in some strange political machinations of their own.

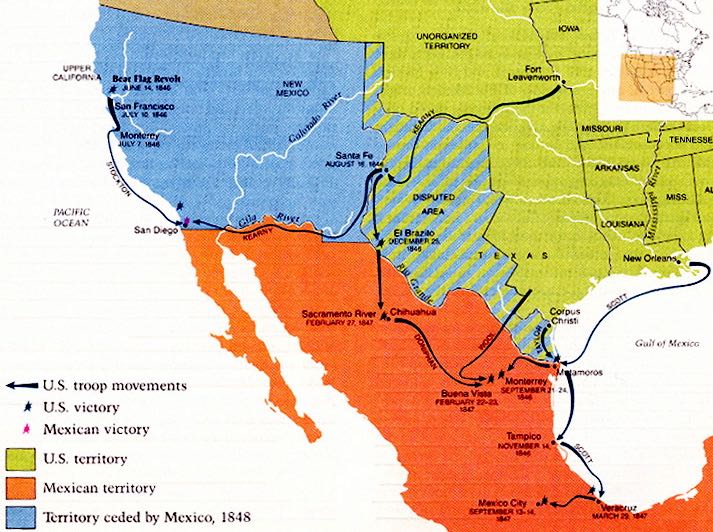

The treaty gave the U.S. the Rio Grande as a boundary for Texas, ownership of California and a large area comprising roughly half of New Mexico, most of Arizona, Nevada, Utah and parts of Wyoming and Colorado. Mexicans in those annexed areas had the choice of relocating to within Mexico’s new boundaries or receiving American citizenship with full civil rights.

The amount of land gained by the U.S. was further increased as a result of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, which ceded parts of present-day southern Arizona and New Mexico.

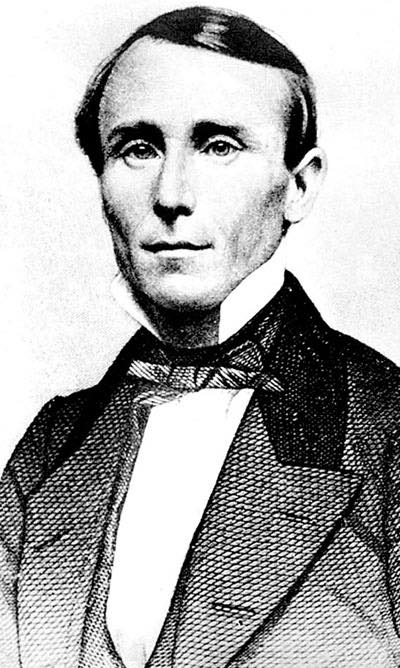

Enter William Walker, filibuster. Today, of course, the term “filibuster” refers to an effort by a minority of U.S. Senators to delay or block voting on a bill or confirmation. The term apparently can be traced back to a Dutch word meaning “pirate.”

William Walker was a filibuster as originally defined. This act of piracy, however, was land-borne and not on the high seas. The term defined adventurers who sought to capture foreign territory without the express authorization or direct cooperation of their governments. They were also called “freebooters.”

Walker, probably the best-known of American filibusters, was a visionary adventurer imbued with the desire to found a colony in Mexico near the American border. His aim was to obtain the independence of Sonora and Baja for ultimate annexation by the U.S. and for the extension of slave-holding into the territory to improve the balance of power for the South.

Walker grew up in Tennessee and was a strong Southern sympathizer. He went abroad in the 1840s to study medicine and was present in Europe during the various revolutions of 1848. These were a series of revolts against European monarchies in Sicily, France, Germany, Italy and Austria. All ended in failure, repression, and were followed by widespread disillusionment among liberals.

There is little doubt that his filibustering schemes were influenced by revolutionary doctrines spreading over the continent. Upon his return, he practiced medicine in Philadelphia, but, finding this unsatisfying, went to New Orleans to study law. He practiced for a short time and then changed fields to become owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent.

The man apparently bored easily. In 1850 he migrated to San Francisco and served as assistant editor of the San Francisco Daily Herald. He was also, obviously, a contentious sort. While in San Francisco he fought three duels and was wounded in two of them.

Walker then conceived his idea of conquering areas in Northern Mexico and the entire Baja Peninsula.

In the summer of 1853, he traveled to Guaymas seeking a grant from Mexico to create a colony ostensibly to serve as a fortified frontier, protecting U.S. soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony.

He began recruiting American supporters of slavery and the Manifest Destiny doctrine. His plans expanded from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually become part of the American Union as the Republic of Texas had done. He funded his project by selling scrips which were redeemable for land in Sonora he had yet to conquer.

On October 15, 1853, the filibuster set out with 45 men to conquer both Sonora and the Baja California Territory. He succeeded in capturing La Paz, which he declared the capital of a new Republic of Lower California with himself as president. He put the region under the laws of Louisiana in order to make slavery legal.

Fearful of counterattacks, Walker moved his headquarters twice over the next three months, first to Cabo San Lucas and then north to Ensenada. Although he never gained control of Sonora, he pronounced Baja California part of the larger Republic of Sonora. Lack of supplies and strong Mexican resistance quickly forced Walker to retreat across the border.

Back in California, he was put on trial for conducting an illegal war in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794. Nevertheless, in the era of Manifest Destiny, his filibustering project was popular in the southern and western U. S. and the jury took eight minutes to acquit him.

Seemingly not knowing when to quit, Walker changed his focus and mounted an effort to conquer Nicaragua, and with some success.

Walker sailed in June 1855 from California to Nicaragua with a small band of armed Californians to join the liberal forces embroiled in a civil war. At stake was access to the trans-isthmus shipping route relying on the huge Lake Nicaragua. After some initial military setbacks, he and his allies took Granada in October and set up a coalition government.

In 1856, Walker declared himself president, re-instituted slavery and made English the official language. U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized his Nicaraguan government.

Efforts to expel Walker and his army proved to be a long and costly. Costa Rica, Honduras and other Central American countries united to drive him out in 1857. During this time, Granada was burned and thousands of Central Americans lost their lives. The final battle of what Nicaraguans call the “National War” (1856–57) took place in Rivas near the Costa Rican border. Walker beat off the attacks, but the effort diminished the strength and morale of his forces and he soon succumbed.

Walker, unable to get his fill, returned to the region once more in 1860. British colonists in the Honduran Bay Islands, fearing that the government of Honduras would move to assert control over them, approached Walker asking for help in establishing a separate, English-speaking government over the islands.

But the filibuster, who’s reputation preceded him, was captured on entering the country. The British executed him by firing squad on September 12, 1860. He was 36 years old.